Ethical Investing: Norway’s Sovereign Wealth Fund

By: Stefanie Hines

Norway’s Sovereign Wealth Fund, officially known as the Government Pension Fund Global (the Fund) is the largest of any nation. The Fund was made possible by the discovery of oil fields just off the coast of Norway in 1969 on Dec. 23rd (Nbim.no)

GPFG owns approximately 1.4% of total global holdings. Worth 1.1 trillion dollars (U.S.) and 8.6 trillion KRON the Fund invests in over 9,000 firms and 72 countries (CNBC 2017). NORGES bank, the central bank of Norway, manages the Fund while the Ministry of Finance acts as overseer.

Source: Economist.com

The closest fund in size in a democratic country is the United States Social Security Trust Fund, which does not hold equities or investments in the private market but rather holds special securities issued by the United States government. (SSA.gov). Norway’s GPFG holdings comprise 66.2% equities, 31.2% fixed-income investments and 2.7% real estate. Apple, Microsoft and Nestle are currently the top three holdings.

The Fund is required to only invest abroad. A standard practice is to only draw on 4% of the generated revenues per year, the fund’s anticipated annual return, for national spending. This rule was enacted to ensure the principal would be safeguarded for future generations.1

History of The Fund: Who Decides What is Ethical?

Profits from the export of oil make the GPFG possible. The Ministry of Finance through an act of Parliament made the first transfer of funds in 1996. Norway’s Fund is unique not only because it is owned by a democratic country but for its ethical stance on investments. The Fund for example has guidelines for companies about children’s rights, climate change and water management. It will not invest in companies that do not meet its ethical standards. The fund also has a process for disinvestment from holdings it believes no longer meet the Funds ethical criteria.

The people of Norway through their Storting (parliament) decided that they do not wish to invest in equities of companies that produce tobacco and certain types of weapons, or those companies which have serious violations of human rights during war or produce severe environmental damage. (Responsible Investment, Norges Bank 2016).

These ethical standards can apply to either the type of production a company does or its conduct. The Fund does not invest in nuclear weapon production companies, anti-personnel landmines, or tobacco production. The Fund also takes a stance against companies that engage forced or child labor, use war crimes to profit, severe environmental danger or other serious “violations of ethical norms” (Guidelines for Observation and Exclusion from Government Pension Fund Global).

Council on Ethics: The Process of Ethical Investment

The Fund’s management team does not make the decision about the ethics of its investments. According to Marthe Skaar the Communication and External Relations manager at Norges Bank: “Ethical discussions are…handled by a separate board and not by Norges Bank.” Skaar refers to the Council on Ethics which is appointed by Norway’s’ Ministry of Finance with recommendations from the Bank.

This council was established by Royal Decree on November 19, 2004. Its predecessor is an Advisory Commission on International Law focused on making sure the Funds’ investments are not in conflict with Norway’s international law commitments. (Chesterman, 2008). The current embodiment of the Council relies on the Graver Report, a multi-agency research effort headed by the Ministry of Finance. Representatives of Norges Bank, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and economic researchers are all cited as having participated in the production.

Graver is the foundational document for the Council on Ethics and its mandate to establish practical ethical guidelines for the Fund (Graver Committee Report)3. The report cites that overlapping consensus and not national culture or policy should drive the ethics of the Fund. The philosophy is best described as a society achieving agreement to a system of governance for different motivations. Some may view ethical investments as the “right” thing to do for humanitarian reasons or other social policy reasons; while investors may prefer transparency and stability. In either of these cases vetted investment universes can satisfy both requirements simultaneously.

Premises and Mechanisms for Fund Ethics

The Graver Committee Report lays out two premises on which to base ethical guidelines: First, the Fund should be an instrument of ensuring future generations see the benefits of the Funds wealth through solid and sustainable returns. Second, the Fund should not make investments that “entail unacceptable risk that the Fund is contributing to unethical actions or omissions…..”3these include humanitarian violations, gross corruption and environmental damage.

The three mechanisms by which the Council should enact these ethical values are: the exercise of ownership rights, negative screening, and the exclusion of companies. Parliament limits the Fund to owning no more than a 5% voting share in any one company2but it is an active voter and has routinely voted against what it sees as unethical or unwise practices such as inflated compensation for CEO’s and has voted for equality among shareholder classes.1

The Fund practices negative screening, a process which screens its current investments for conflicts with its ethical criteria to recommend disinvestment. In the past, this task has been delegated to outside research firms like the Ethical Investment Research Service.2Should the screening reveal conflicts between the Funds principles and the investment being adjudicated the Council will propose exclusion from the fund or disinvestment. It is the fund managers at Norges Bank who will act on these recommendations from the Council.

Ethical Controversies: How the Fund Disinvests

Once the Council determines exclusion of a company or disinvestment of a currently held company the Fund sends a letter to the firm affected, stating its concerns on the firm’s ethical practices, the Fund’s intention to disinvest and invites the firm to respond. This is intended to give the firm a chance to explain why the Council’s decision is ill founded or misinformed.

The Fund is not bound to accept or acknowledge the firm’s answers to its concerns. It should be noted here that it would not be reasonable or in compliance with the first premise of the Fund’s ethical guidelines to disinvest from a company with a solid return and in compliance with its ethical practices. The Fund has every incentive to listen to a firm’s explanation or even plan for remedy before disinvestment as long as reasonable returns are present.

The Fund’s disinvestment practices have garnered some criticism over the years from both academic and political actors. Simon Chesterman, Dean at the National University of Singapore, is critical of both the foundational principles of the Council and on the structure of its decision-making process, including the choice to announce disinvestment from excluded companies after the disinvestment has taken place.

Chesterman cites that both overlapping consensus and the UN Global Compact are used to justify disinvestment when the Council wishes to avoid complicity in human rights abuses or other unethical behavior. He notes that the council avoids defining the “unacceptable risk of complicity….” in unethical behavior through investment. Chesterman’s critique lies not only with what he describes as a “quasi-legal” system with “….no real fear of formal review.”2but also with the idea of public disclosure of its disinvestment after the fact. The Fund does publish its reasons for disinvestment after the transactions have already been completed.

The practical reason for announcing disinvestment after the fact is to prevent a drop in the value of the equity being disinvested which would violate the mandate for the Fund to achieve the best return possible. Chesterman doesn’t have any arguments with the practice of disinvestment but of the public announcement after the shares have been sold. Chesterman argues that if the disinvestment were to take place and remain private the mandate of ethical investment is met but publically announcing disinvestment can affect shareholders and other stakeholders in large firms. This result gives rise to other ethical questions.

The exclusion of Walmart the largest U.S. employer drew heavy criticism from U.S. Ambassador Benson K. Whitney who accused the Fund of “sloppy screening” and asked the Norwegian Fund to consider not only the “….large mutual funds but the small investors and employees….”2

The Fund is fully transparent in its reasoning on the exclusion of Walmart and its subsidiaries listing its rationale on its webpage on exclusions.4 The Fund cites use of child labor, hostility to unions and other labor rights issues as its basis for exclusion. The Council on Ethics goes on to say that the case of Walmart is special because of “the sum total of ethical norm violations, both in the company’s own business operations and in the supplier chain….”4This reasoning is clear and well defined though the guidelines themselves may be open to interpretation.

Despite the critiques of Chesterman and Whitney the Fund’s guidelines carry out the will of the Norwegian people and support their ideals to withdraw support from those organizations deemed misaligned with its values. Requiring justification from a sovereign fund whose processes and decisions are transparent is unnecessary. The people of Norway are free to support their values in the same way any investor is; to propose otherwise is anathema to a free global market.

GPFG’s Strategy on Climate Change

Dr. Heidi Nilsen, an economic researcher at the Centre for Ecological Economics and Ethics at Bodo Graduate School of Business in Norway, points out that in 2010 Norway did not recognize contributions to climate change as producing “severe environmental damage”.5Does the Fund make this exception because its wealth comes from oil production? 3% of total global emissions come from oil production and transportation.5

Unfortunately comment on this issue was not forthcoming either in 2010 or today. Nielsen states the fund has a “lax practice with regard to mitigating climate change.”5Since 2010 the Fund has laid out its expectations for climate change risk mitigations from companies and list numerous guidelines and strategies on its website6.

These include the call for sustainable growth from companies currently engaged in deforestation, coal production and other high emissions sectors. Changes to the Fund in 2014 produced new rules for exclusion and observation were added. Companies which control assets or receive more than 30% of their income from thermal coal will be excluded from the fund. Oil production and emissions are not mentioned in the exclusionary rules.

Nielsen’s’ criticisms are along the same lines as those of Whitney and Chesterman on the subject of ethics. Nielsen states that “the priority of consequentialism before deontology must be changed”6. Dr. Nielsen believes that overlapping consensus is not the correct philosophical framework to address the very real issue of climate change. Value based arguments she posits would be more effective at seeking the radical changes climate change mitigation policy needs. The Fund has laid out its expectations towards companies but it is still unknown how aggressively these expectations will be enforced or by what mechanism.

Management of the Fund: People and Earnings

Yngve Slyngsta is the CEO of Norges Bank Investment Management and began his career as a researcher in 1993. The rest of the Executive Board is made up of 7 board members, (5 men and 2 women) and two alternates and two employee representatives. This sort of gender representation is often unheard of in high level Wall Street positions or even in financial arms of the U.S. government. Though it should be noted that this diversity does not exist on the Investment Management Leader team for the GPFG.

To incentivize good business practices, performance pay is based on longer time horizons, including claw back clauses if employees are found to have made overly risky decisions and performance pay is not given to those leaving the company. This policy prevents those with investment power from only seeking short term gains to boost their personal wealth while disregarding the soundness of the investments. (Employee Compensation Structure)7 These practices are thought to lead to more sound investment strategies in the long run and prevent corruption and instability.

The members of Norges Bank Investment Managements Leader Group are not allowed to receive performance pay. Investment personnel who are eligible for performance pay have these bonuses structured around a two year moving average. Performance pay is also paid in installments over a three year period and dependent on the absolute return of the Fund. These safeguards are to incentivize responsible investing while rewarding performance.

Changes in Risk Preferences: Low Oil Prices May Require Higher Risk Profiles

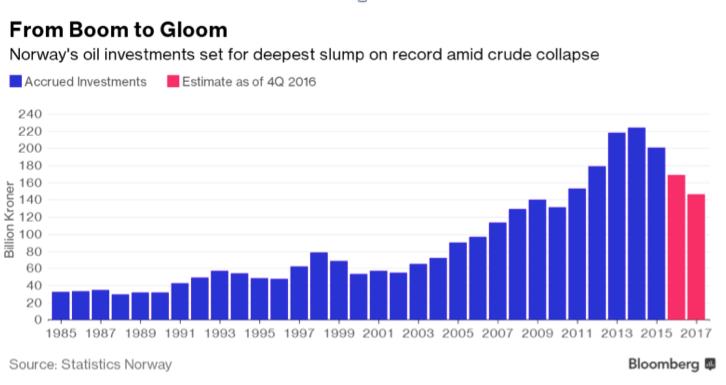

As natural gas and other oil alternatives began to arrive on the scene oil prices dropped, drastically effecting oil rich nations like Norway. Siv Jensen the Norwegian Finance minister told CNBC in February 2017 that “returns are likely to be lower going forward…” Norway may be faced with lower returns if lower oil prices and continued volatility occur. (CNBC 2017). Finding new investments with returns like those of previous years and meeting the fund’s ethical guidelines may prove difficult in the coming years.

Some experts like Sony Kapoor, the managing director of think tank Re-Define believe Norway is exposing itself to great risk by being heavily invested in US tech companies that often use offshore tax havens to shield profits. Kapoor believes the heavy investment in these companies exposes the Fund to too much risk should these tech companies be compelled to repatriate their profits or through fines or taxation in the holding countries. (Kapoor 2017-Tax Havens)

Kapoor believes that Norway has missed a great opportunity to invest in unlisted infrastructure projects and emerging economies in African and Southeast Asia, two areas with the highest growth potential. Kapoor states the GPFG is uniquely situated to take on more risk because of its infinite time line. He believes the Fund has a duty to foster growth and direct investment capital in underfunded economies around the world. This seems to be a quandary for the Executive Board who reject the idea of investing in unlisted infrastructure projects due to their riskiness.

This strategy however, fits in directly with the fund’s ethical stance on climate change and human rights. By becoming a large investor in such places, it could promote ethical job creation and ensure localities which receive direct funding create and comply with prudent environmental regulations. Kapoor argues that by not doing so the fund violates its own ethical code. (Kapoor 2017-Investing for the Future)8

Norway’s sovereign wealth fund has a history of earning solid returns on its investments: 5.9 % annualized since 1998 with an annual management cost of 0.08%9. The highest returns in 2017 were from equities (19.44%) and the lowest from fixed income investments (3.31%).

The Fund’s ability to find reliable and lucrative investments is not in question. Kapoor’s theory of regulatory exposure in U.S. tech companies is exaggerated, as regulatory bodies in the United States have no desire to increase taxes or regulations. Further his idea that unlisted infrastructure projects somehow pose less risk than listed equities is unfounded and may violate one of the Fund’s mandate to ensure it seeks the best possible return for the people of Norway.

The GPFG of Norway is a proven if imperfect example of an investment vehicle used to promote the social values of the people it represents. Chesterman and Nielsen may be correct in their assertions that overlapping consensus is not the ideal framework for the guiding principles of the Fund and that clearly defined value based decisions better fit the mission of ethical investment. This may be ideologically correct but real change occurs when firms have monetary incentives to make changes to their business models. The threat of exclusion or disinvestment is real and felt not only by the firms themselves but the industries and the political economies in which they operate.

The Fund’s continued commitment to transparency in its processes and reasoning should be seen as an effort to hold open dialogue with investment communitites and a movement toward perfect information. Its reluctance to omit oil producing companies along with thermal coal production firms is questionable but arguably in line with the mandate to create the highest returns possible. The practices of fund risk management, thoughtful ethical guidelines and transparent operations have proven that funds can operate ethically and earn reliable returns for their investors.

References

- 1. https://www.nbim.no/en/the-fund/

- Chesterman, S. (2008). “The Turn to Ethics: Disinvestment from Multinational Corporations for Human Rights Violations – the Case of Norway’s Sovereign Wealth Fund,” American University International Law Review, 23(3), 577-615.

- Graver Committee Report-https://www.regjeringen.no/en/dokumenter/Report-on-ethical-guidelines/id420232/

- https://www.regjeringen.no/no/aktuelt/two-companies—wal-mart-and-freeport—/id104396/

- Nilsen, H. (2010). “Overlapping consensus versus discourse in climate change policy: The case of Norway’s Sovereign Wealth Fund,” Environmental Science and Policy,13(2), 123-130.

- https://www.nbim.no/en/responsibility/risk-management/climate-change2/

- https://www.nbim.no/en/the-fund/governance-model/executive-board-documents/principles-for-compensation-to-nbim-employees

- https://redefine.org/sites/default/files/sites/default/files/images/OilfundFinal.pdf

- https://www.nbim.no/en/the-fund/return-on-the-fund/

Photo: CNBC.com