Ethics Review of Green Bonds

By Nathan Chua

Part of Seven Pillars Institute’s series on Climate Finance (CliFin)

Among climate finance instruments, green bonds have a positive future. There should be greater efforts to address concerns about the transparency and accountability of green bonds issuers and to measure the impact of this method of climate financing.

Climate Change and Climate Finance

Climate change is described by Stephen Gardiner as a “perfect moral storm” because it brings together three major challenges to ethical action in a mutually reinforcing way: (1) its global nature resulting in the “Prisoner’s dilemma”, (2) the existence of intergenerational equity, and (3) the difficulty in determining the appropriate relationship between man and nature. Together, these challenges make climate change a complex issue, with the United Nations labelling it as the “defining issue of our time”.

In 2019, extreme weather conditions as a result of climate change affected every single inhabited continent of the world. With droughts plaguing sub-Saharan Africa, tropical storms sweeping across Southeast Asia and most recently bushfires raging across Australia, the climate crisis in 2019 attributed more than fifteen $1 billion plus to disasters. Hence the need to overcome this “moral storm” and implement real impactful change now, has never been more important.

Effective mitigation of climate change requires aggressive, collaborative action from all stakeholders in the world. However, with current global tensions, this is evidently improbable. Therefore, individuals and non-governmental organizations have taken action by developing and implementing new initiatives such as climate finance and green bond investing.

Climate finance (CliFin) as defined by the Seven Pillars Institute refers to “Any financial service, instrument, vehicle, or even regulation designed to mitigate, or adapt to, the effects of climate change”. The United Nations has also coined its own definition for climate finance, referring to it as “Local, national or transnational financing—drawn from public, private and alternative sources of financing—that seeks to support mitigation and adaptation actions that will address climate change.” Though the definitions vary slightly, they both include the implementation of finance and funding practices to provide improved opportunities and capacity for climate change mitigation.

Green Bonds

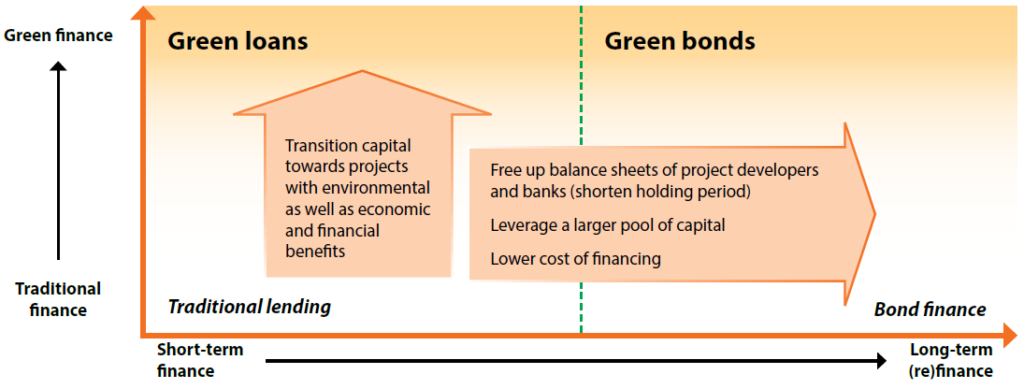

Falling within CliFin are green bonds.

Bonds are tradeable fixed-income debt instruments that provide issuers with access to funding from international and domestic markets. Bonds are an alternative to traditional bank loans, whereby the issuer, instead of paying back a loan to a bank, will need to repay back the cost of the bond to the investor. Both methods issue over a predetermined time period and charge interest. Anyone can buy bonds, though issuers of bonds will usually be governments, corporations or multinational banks.

Project Bonds began in the early 1990s when sponsors of large projects (mainly in the infrastructure field), utilised bond markets to access long term fixed rate debt financing. The sponsors as issuers, had the ability to set the bond term and hence chose to repay investors over a longer term with fixed interest rates. This agreement was mutually beneficial to institutional investors such as insurance and superannuation funds[1] who sought stable returns over longer maturities and more diversified investment portfolios. At the time, new structured credit techniques such as limited recourse financing methods also allowed projects to be de-risked, making bonds attractive to investors.

Green bonds are a recent adaptation of “Project Bond”, with the distinguishing feature being that the bonds are issued for the sole purpose of funding projects that help with climate change mitigation, energy efficiency and environmental sustainability. These projects range from the adaptation of the Great Barrier Reef to warmer waters, to building Nile Delta flood defences. Green bonds typically carry a lower interest rate to reflect lower risk as most green projects occur in their operational, rather than construction phase.

The ICMA is a not-for-profit membership association with more than 580 members in 62 countries. Its members include private and public sector issuers, banks and securities houses, asset managers, capital market infrastructure providers and law firms. Its aim is to inform members of regulatory and market practice issues, provide services in international capital and securities markets and to issue rules and recommendations governing their operations.

The ICMA issues Green Bond certification and has created a list of categories green bond projects serve. These include but are not limited to:

- Renewable energy

- Energy efficiency

- Pollution prevention and control

- Environmentally sustainable management of living natural resources and land use

- Terrestrial and aquatic biodiversity conservation

- Sustainable water and wastewater management

- Clean transportation

- Climate change adaption

- Eco-efficient and/or circular economy adapted products, production technologies and processes

- Green buildings

Growth of Green Bonds

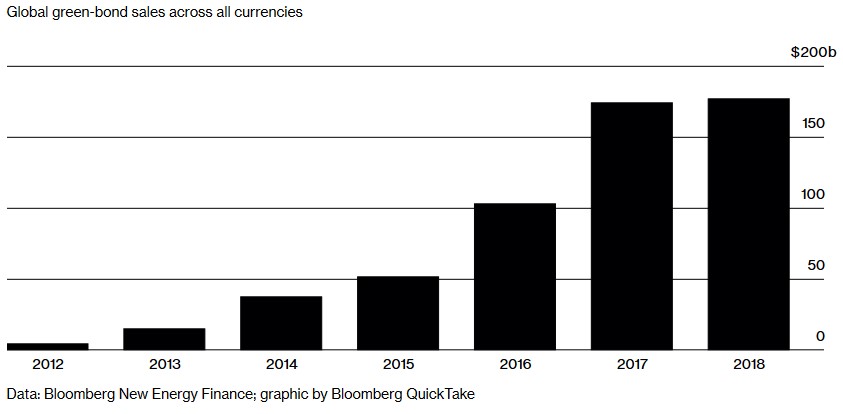

The green bond market has rapidly expanded since its inception. These bonds were first issued in 2007 by the European Investment Bank, followed by the World Bank in 2008. At the time these were the only fixed income, socially responsible investment products. In 2012, green bond issuance amounted to only $2.6 billion but by 2014 annual issuance was at $37 billion. In 2016, $70 billion of green bonds were issued and approximately $157 billion was issued in 2019. A diverse range of issuers became part of the green bond movement with Apple and Poland, both issuing green bonds in 2016. As of 2019 there have been issuers from more than 50 countries. The US is currently the largest issuer, followed by the mortgage company Fannie Mae.

Source: Bloomberg

Investment incentives

Despite researchers finding that green bonds when compared with other bonds issued by the same municipality, have an average yield of 6 basis points higher than self-identified green bonds, and up to 20 basis points higher for certified green bonds, they have grown tremendously. This highlights that investors are placing a premium on green bonds and are willing to accept lower rates of return in exchange for the environmental benefits its provides.

The Global Financial Crisis (GFC) forced stricter regulatory requirements on banks. Accords such as “Basel III” have resulted in higher costs and increased capital requirements for banks, who have subsequently passed these expenses onto their customers. Many project sponsors have begun diverting resources away from traditional debt finance into more innovative and sustainable sources such as project and green bonds.

Summary of Pros and Cons of investing in Green Bonds

Positives

- Gives investors opportunity to make profits while supporting positive environmental, social, and governance causes (ESG) at the same time

- Can provide financing options to projects which would otherwise not have any, especially in developing countries

- Ability to source funds from a large international market

- Will grow substantially in the next few years

- Bonds often provide tax incentives or tax credits

- Provides opportunity for investor diversification

- Provides reputational benefits to issuers as well as marketing to invested projects

- Frees government balance sheets and can help countries achieve global commitments

Negatives

- Issuances that are small are less attractive to investors as they have relatively higher costs as proportion of total proceeds.

- Green bonds, to be successful, require efficient coordination across market players in the private and public sector

- Generally higher costs due to transparency and accreditation expenses

- Relatively new market means there is not currently an international authorising body, though there are some organisations that do this independently

- Many ethical considerations that have yet to be explored as it is a relatively new market

Source: Climate and Development Knowledge Network

Green Bond Ethics

Individual Responsibility

Green bonds are closely tied to climate change ethics as every single person in the world regardless of background, has a moral obligation to address this environmental crisis. Due to the substantial harm climate change will inflict on the human and nonhuman world, it is critical that we as contributors to this change are aware of and make appropriate steps to mitigate it.

Green bonds provide issuers with the opportunity to deliver corporate social responsibility and provide real climate change alleviation through actual action carried out in invested projects. Global investors on the other hand, are given the option to invest their own money in positive and ethical climate change practices and as a part of their global responsibility, make their own beneficial contribution to the world.

Global Responsibility

Ethical responsibility also falls on countries who, as part of multinational organisations, have agreed to achieve certain climate change targets by specific dates. The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development adopted by all United Nation member states in 2015, outlines 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) to be achieved through global cooperation. These goals include affordable and clean energy, sustainable cities and communities and climate action.

However the United Nations has currently estimated that an additional $2.5 trillion is still needed annually to fund the achievement of these goals and within this, $1 trillion is needed for clean energy alone. The many projects which are designated to help to achieve these 17 goals cannot continue with or begin operation unless new sources of finance such as green bonds are mobilised.

Since public sector balance sheets also do not have the capacity to finance all of the projects required, an estimated 80–90% of funding will need to come from the private sector. Within the private finance industry itself, banks can also only take on a certain amount of debt before capital markets will have to be leveraged. Hence governments that have agreed to such goals and are morally obliged to achieve them, should begin exploring adequate ways to do so. By perhaps tapping into new opportunities such as green bond markets and increasing awareness, the financial burden can be partially lifted.

Certain countries have already begun implementing national-level guidelines and standards for green bond issuance to prepare for the future and to meet their commitments. For example, Nigeria’s Government is currently working with the Green Bond Private Public Sector Advisory Group (GB-PPSAG) to develop green bond guidelines in preparation for the planned domestic issuance of sovereign green bonds. The guidelines will include information on the relevant targets under the United Nations Nationally Determined Contributions (NDC’s) for each project type.

NDCs set out by the Paris Agreement in 2015 require each country reduce national emissions and adapt to the impacts of climate change by preparing, communicating and maintaining the successive contributions that it intends to achieve. Nigeria has already decided to focus specifically on the areas of environment (reforestation), agriculture (biofuels) and power (off-grid solar).

Brazil has also started developing its own Green Bond Guidelines in conjunction with Brazil’s banking federation (FEBRABAN) and the local Business Council for Sustainable Development (CEBDS) in order to grow the domestic green bond market. Hence countries require cooperation from not only the public sector but also the private sector to ensure that green bond markets operate efficiently and targets are met.

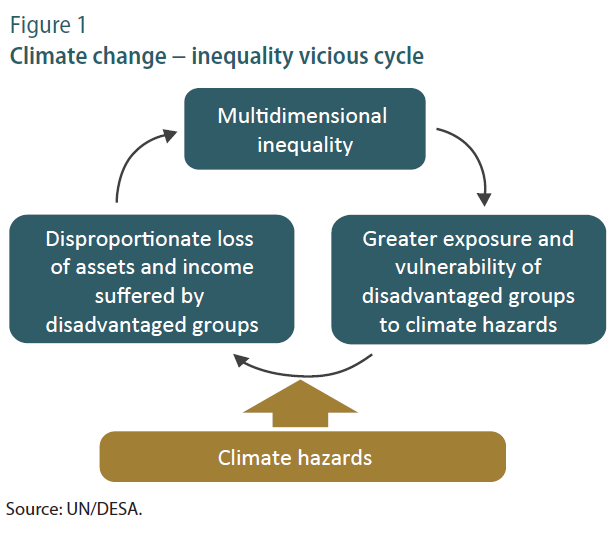

Inequality

Climate justice refers to the disproportional impact of climate change on poor and marginalised populations. The United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs characterises the relationship between climate change and inequality as “A vicious cycle, whereby initial inequality causes the disadvantaged groups to suffer disproportionately from the adverse effects of climate change, resulting in greater subsequent inequality.” All citizens of wealthy and industrialised nations therefore have an obligation to reduce extreme poverty as they are the only ones with the capacity to do so.

Green bonds have the capacity to reduce income inequality as they provide long-term financing for projects in locations where access to long-term bank loans can be limited. In developing countries, green bonds are already financing many critical projects, including urban mass transit systems and water distribution. Emerging and developing countries which have lower project costs also have the highest environmental impact per unit of currency. Though it may take years to see quantifiable change, by investing in projects that reduce climate change whilst building sustainable infrastructure that improves welfare, individuals are effectively solving two of the world’s greatest ethical challenges at once.

For example in Nigeria, 10.69 billion naira green bonds have already been issued. The funds have been distributed across three different projects, in alignment with 8 of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals of the United Nations. Projects such as the Renewable Energy Project Micro-Utilities provide electricity access to 45 previously unserved rural communities. The initiative has given employment and income to people who are now required to maintain the new mini grids as well as increased standards of living for the community through new electricity access (IOE, 27).

Another project called the Energizing Education Project in Nigeria has generated sustainable and clean power to 37 Federal Universities and 7 University Teaching Hospitals across the country, helping to increase the educational standards of the country and create a more employable and dynamic workforce for the future.

Regulation

There are ethical issues surrounding the misuse of the term “Green Bond”. To qualify for green bond status, bonds are verified and audited by a recognised independent party such as the Climate Bond Standard Board, which certifies the bond as funding projects that mitigate climate change. The most commonly accepted institutions accrediting bonds to be green are the International Capital Market Association (ICMA), and the Climate Bonds Standards of the Climate Bonds Initiative (CBI).

However, if there is no independent body auditing a company’s issuances, investors may often be misled by those who choose to abuse the use of the “Green” name status. This practice of falsely claiming green status is termed “Greenwashing”. The International Capital Market Association outlines Green Bond Principles, guidelines that recommend transparency, disclosure and reporting.

According to the ICMA Green Bond Principles the bond must align with four core components:

- The use of proceeds: Transparency in the utilisation of bond proceeds in green projects

- Process for project management and selection

- Issuer of green bond should clearly communicate to investors:

- The objectives for environmental sustainability

- An explanation of how the invested projects fit within the eligible green bond categories

- The related eligibility criteria as well as exclusion criteria and material environmental and social risks associated with the projects.

- Issuer of green bond should clearly communicate to investors:

- Management of proceeds: The net proceeds of the Green Bond should be credited to a sub-account, moved to a sub-portfolio or otherwise tracked by the issuer in an appropriate manner. This process should also be attested to by the issuer in a formal internal process linked to the issuer’s lending and investment operations for Green Projects

- Reporting: Issuers should make, and keep, readily available up to date information on the use of proceeds. Information should also be renewed annually and on a timely basis.

These standards should apply to all issuers. However independent third-party verification is often not needed for ‘purely green’ businesses. These include companies that have been created solely for the generation of renewables, companies with strong green bond track records and those with high levels of transparency. This transparency may be from a Climate Bonds Initiative (CBI) certification or positive post-issuance assurance from a known supplier.

As green bonds are still relatively new, there are areas of exploitation and ethical ambiguity. Investors should be wary of potential loopholes and try purchasing from issuers that hold noteworthy accreditations or are listed on reputable markets. For example, to issue green bonds on the London Stock Exchange (LSE), a standard prospectus will not be enough. The LSE requires the issuer also provide a relevant “second opinion” document that certifies the ‘green’ nature of the bonds. Though the issuer can pick its certifier, the certifier should meet stringent criteria before the green bonds can be included in the relevant LSE green bond segment. Segments available for inclusion include the Orderbook for Retail Bonds (ORB), Orderbook for Fixed Income Securities (OFIS), and Trade Reporting only segments. As the LSE holds a sophisticated and mandatory listing process requiring extensive legal certification, the issuers on this exchange will generally be more ethical in approach (LSE, 28).

Credit Ratings

Credit rating agencies undertake independent creditworthiness investigations to inform investors of the relative risk profiles of investments such as bonds. The presence and standing of credit rating agencies varies in different markets but they must have international credibility and be active in bond ratings for their assessments to be taken into consideration. Large rating agencies in addition to their core credit rating services have begun opening up new service lines solely for assessing green bonds. For example, Moody’s Investors Service offers a green bonds assessment, and Standard and Poors (S&P) has set out plans for a new green bonds evaluation tool. If a company and its green bonds have credit ratings from non-credible institutions there is risk for unethical valuations as well as inaccuracy. Hence investors should be more careful, as well do extensive research before investing, especially if the company is unrated.

The world’s three largest credit rating agencies, Standard & Poor’s, Moody’s and Fitch Ratings hold a combined total of 95% of all global credit ratings. Despite their complicity and ethical failings that contributed to the GFC, receiving a credit rating for a green bond from one of these organisations is, sadly, probably the best one can rely on, in terms of evaluating creditworthiness.

The Case of Woolworths: Green Conflict of Interest

There are many ethical considerations regarding the type of projects chosen, and the way in which projects are carried out. For example, a downside of the green bond process is that finances gained out of issuance are often used to refinance an asset that has been built up using finance from mostly non-green sources. The initiation of a project could inadvertently cause even greater environmental damage through the sourcing of its resources from unsustainable suppliers. Additionally, many companies are choosing to reduce their carbon footprint, rather than eradicating it or are spending the bond issuance money on areas that are seen as immoral.

For example, Australian retailer Woolworths Group raised $400 million Australian dollars in early 2019 through green bond issuances and promised to use the proceeds to develop low-carbon supermarkets specifically via the:

- Installation of solar panels on the roofs of Woolworths supermarkets and distribution centres

- Retrofitting of energy-efficient LED lighting within stores

- Installation of fridges with hybrid or Hybrid Fibre Coax-free (HFR-Free) refrigeration systems

- Installation of Solar and TESLA battery systems in Erskine Park’s liquor distribution centre

- Reduction in use of plastic wrapping for fruit and vegetables

In doing so it became the first retailer in Australia, and the first supermarket globally, to issue Green Bonds that have been certified by the Climate Bonds Initiative (CBI) (Woolworths Group, 29). EY was the company that certified in a “reasonable assurance” statement that Woolworths met the ICMA and CBI standards. It also examined Woolworths’ published framework for how it would use the money (Woolworths Group, 30).

However, there is currently an ethical issue with Woolworths’ other investments. Woolworth currently owns the ALH Group gambling business and the BWS and Dan Murphy’s liquor chains. Investing in Woolworths’ green bonds means providing project renovations such as light bulb refitting to casinos and alcohol stores. These renovations could then promote the attractiveness of these stores, causing an increase in gambling and alcoholism. Hence, there is a conflict of interest on whether to place higher emphasis on climate change mitigation or on other moral concerns such as encouraging alcohol use and gambling. Many prospective investors such as the financial services firm Perpetual Limited have passed on Woolworth’s green bond offering for this reason. Woolworths has reportedly begun plans to remove all of these businesses from its global conglomerate.

Green bond money is also often spent on projects which will improve the environment regardless of whether or not there is access to green bond finances. Woolworths, for instance, suggested that it might spend some of its green bond money on the “Development of low-carbon supermarkets” , which are essentially new supermarkets whose emissions are relatively low and decline over time. However, since lowering a supermarkets’ energy use can raise the owner’s profits substantially, supermarket groups in many districts have already begun reducing their energy intensity regardless of whether the green bonds are issued or not. Woolworths is effectively using the green bonds initiative as a masquerade to fund projects that would happen anyway and utilise the funding to increase its own profits. The profits could then be invested in other unethical or environmentally hazardous areas.

The Climate Bonds Initiative’s (CIB) Chief Executive, Sean Kidney has stated that under the Paris agreement, 40 per cent of carbon emission reductions must come from improving the built environment. He states that retailers have a large role to play in achieving those targets. Woolworth’s challenges highlight the ethical considerations when issuing green bonds, especially for the first time in new countries or markets.

China and Green Bonds

Another example of this problem involves China, the world’s biggest carbon emitter and second largest green-bond issuer. The country faces criticism for using green bonds to finance coal-burning power plants. Although these power plants were installed with new greener facilities, they still emit excessive levels of greenhouse gases. According to The Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis, the Chinese government has now decided to remove the ‘clean coal’ definition from its green bond guidelines. This new definition will hopefully align more closely with the European Union Climate Bond Standards and win it more international investors. The Chinese example illustrates how investors have the power to change an issuer’s processes. However, if no information is known or released, then nothing can be done and issuers will unethically continue with environmentally damaging practices.

Identifying Impact

There needs to be greater transparency regarding the distribution of net funds to green projects after operational expenses have been accounted for, how the projects spend the allocated funds and the level of impact each project creates. If issuers state their green bonds as funding green projects, there is an ethical responsibility of the issuer to understand and collaborate with the projects it is funding.

This process will often require empirical evidence and data to satisfy and guarantee investors that quantifiable change is made. However this often requires the use of experiments and control groups. Accurate and precise evaluations will take time and money, and the results may often be disappointing or unavailable before the bonds come due. If this happens investors may feel let down, stopping their future investments in green bonds or they may even sue issuers.

Diversity in Investments

Another concern is with regards to how only certain types of projects are tackled whilst others are neglected. For example, most companies focus on projects providing renewable energy rather than tackling waste and pollution, causing an uneven distribution. Many areas that are critically important are being neglected due to greater costing requirements. For example a business did not invest in a project related to sustainable water as the project did not help the business in any way, even though the geographical location desperately needed sustainable water. If there is no authority to enforce or promote the need for a more even distribution, then there may be large climate change projects and places that are catastrophically neglected.

According to the European Commission, distribution of 2015 green bond financed projects were as follows:

- Renewable energy (45.8% )

- Energy efficiency (19.6%)

- Low carbon transport (13.4%)

- Sustainable water (9.3%)

- Waste & pollution (5.6%)

These statistics highlight vast distribution differences. Although any climate change mitigation is beneficial, for specific countries and cities, focusing on one area may be more critical than others. For example, Shenzen, China which relies heavily on coal burning for its electronic manufacturing industry may avoid transitioning to cleaner renewable energy as it will take implementation time and may reduce the production output and overall efficiency of the industry. This in turn affects the country’s economic growth and competitive advantage in manufacturing cost. Green bond projects may be avoided in these renewable areas where it is actually needed the most, ultimately harming the world and demonstrating an avoidance of ethical and social responsibility.

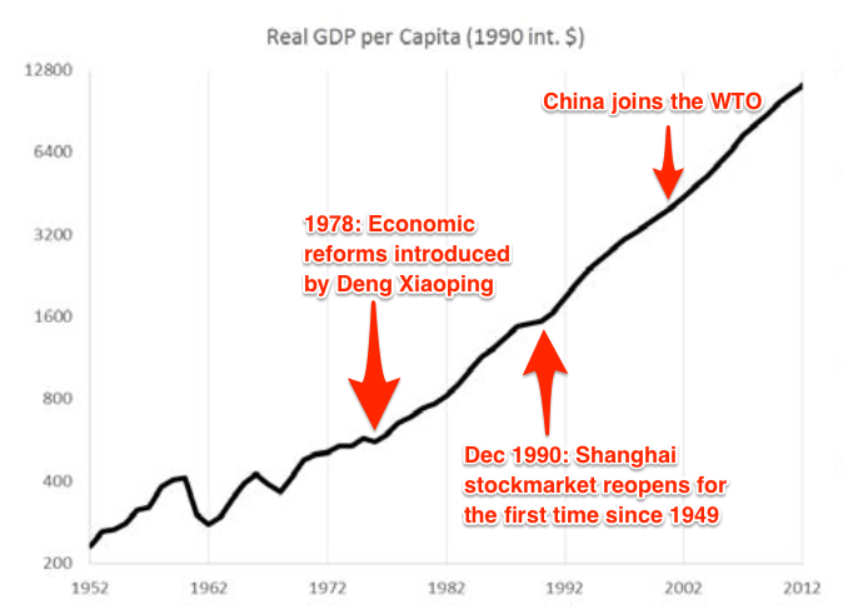

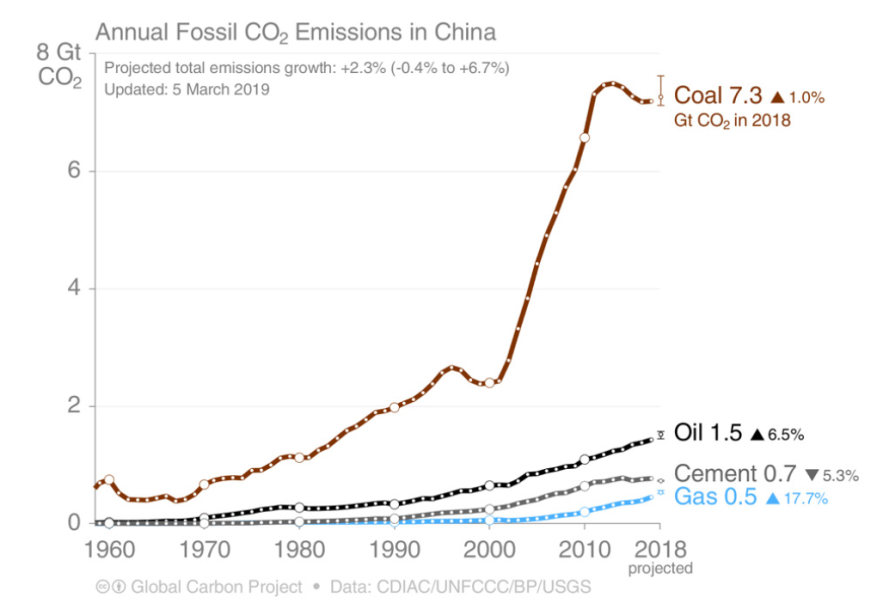

Once again, this illustrates the difficulty in balancing economic growth and sustainability, with China as a modern day example. The country’s high air pollution levels from its “Reform and Open Policy” in 1978, which introduced a new era of rapid and ambitious economic development, has placed a heavy burden on the ecological system (Science Direct). China’s emphasis on economic growth continues to this day at the expense of its own atmosphere and environment.

Source: World Economic Forum

Source: Cabonbrief

The credit rating company, Moody’s Investors Service, reported that in December 2018, renewable energy only claimed 17 percent of green bond financing, clean transport 15 per cent and 52 percent was spent on making new buildings or on improving efficiency of existing ones. According to the Dutch bank ABN AMRO, real estate in the Netherlands is responsible for 40 per cent of its carbon emissions. The dominance of green bond building projects at more than 40 percent on average highlights how companies choose to invest in easier projects since building assets are easily accessible. This is again a misplacement of responsibility for what may be potentially needed within a certain country or economy.

Green Bond Information and Awareness

There are currently concerns regarding the information being distributed by issuers to individuals. For green bonds to be a driving force of climate finance and environmental transformation in the future, there should be a mandatory international system or international authority to secure investor protection and confidence. These systems should both accredit issuers as well as provide knowledge and education to worldwide audiences regarding proper practices and the importance and practicality of green bonds.

The European Union is currently developing a Green Bond Standard, which will build on current market practices, including the ICMA Green Bond Principles. If an issuer’s plans are independently verified by an EU-accredited assessor they will be able to cite compliance with the EU standards. However, adhering to the compliance standard is voluntary rather than legally binding and not so different to the ICMA or CBI accreditations currently available in the market.

Since large bond issuance and investment rely largely on an unrestrictive political environment with supportive policies, regulation and tax regimes, many companies may unethically bribe governments or credit agencies for accreditation and support. There is a drastic need for international accountability via an international standardised authority.

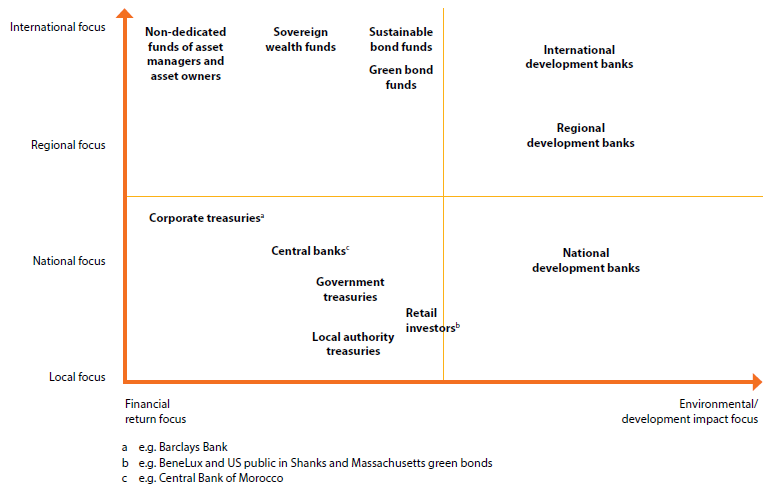

There should also be a culture within the community that promotes green bonds as an investment option for people from all walks of life rather than just mainstream institutional investors, specialist responsible investors and corporate treasuries.

Currently green bonds additionally require enhanced levels of transparency regarding the “use of proceeds” and have sophisticated reporting requirements that incur increased costs as opposed to “vanilla” bonds.

Investment relies largely on people who have the capacity to pay for extra costs and those who place greater emphasis on climate change mitigation over monetary benefits. Not everyone has the capacity or desire to do this and hence issues regarding climate equity also begin appearing for green bonds in relation to the extent that individuals with greater wealth and opportunity bear greater responsibility for climate change mitigation.

Green bonds therefore typically come with incentives such as tax exemption or tax credits to enhance their attractiveness to investors. Additionally, the more popular green bonds become, it will have higher investor demand and relative scarcity which will increase the bond’s price in secondary markets to give investors greater long-term returns.

Future of Green Bonds

As the world increasingly suffers from climate disasters, the importance and urgency of climate action becomes ever greater. So does our ethical responsibility to act. A report released in November 2018 by Edelmen PR Group found that nearly 90 percent of institutional investors across the world had changed their voting or engagement policy preferences in the previous 12 months to pay more attention to environmental, social and corporate governance (ESG). Emma Herd, CEO of the Investor Group on Climate Change (IGCC) stated that European investors are “aggressively looking for green bonds” and New South Wales Treasury Corporation’s (TCorp) Katherine Palmer noted higher green bond demand from both small and large investment funds. Eden Wong, chairman of the Green Park Financial group, has also stated how institutions in countries like Hong Kong are now aware they need to be environmentally conscious. The trend is growing for all stakeholders in the world to recognise their individual responsibility.

Malcolm Baker and George Serafeim in a report for Harvard Business review have stated how green bonds have a positive future ahead and may even be our best bet for environmental damage control. With the exponential growth green bonds have experienced in such a short timeframe and with the increasingly evolving technological capabilities of the 21st century, it it is likely green bonds will play a major role in the world’s future economy. It is always important consider the ethical implications and exploitations evident within the green bond market. Investors should not lose sight of the climate change mission, but like any responsible investor, always remember the reasons why they want to invest and the benefits that it creates for themselves and the world.

-x-

[1] In Australia, the Government has a compulsory superannuation policy whereby all employers must pay a percentage of an employee’s total earnings into their elected superannuation fund. This is to ensure that by the time the employee retires, the super fund will provide them with sufficient regular income. The mandatory contribution amount is currently at 9.5% of total income (Feb 2020), including bonuses, commissions and loadings, though this can be increased. Over the course of someone’s entire working life, contributions accumulate and are invested by elected superannuation funds to generate greater returns.