Ethics Review of Carbon Taxes

By Cassie Ransom

Introduction: Climate Finance and Ethics

The effects of climate change are becoming increasingly apparent. In 2020, wildfires in California and Australia and cyclones in Bangladesh and India caused mass destruction of infrastructure. United Nations Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon (2015) said, “Climate change is intrinsically linked to public health, food and water security, migration, peace, and security. It is a moral issue. It is an issue of social justice, human rights and fundamental ethics. We have a profound responsibility to the fragile web of life on this Earth, and to this generation and those that will follow.” Addressing climate change is thus not only a technical and political challenge, but an ethical one.

Reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions may be the most imperative measure to prevent further global warming. The Paris Climate Agreement (2015) is a legally binding international treaty between 196 parties which sets targets on emissions reductions. Countries must formulate and implement their own schemes for reducing emissions to prevent the world’s global temperature from rising above 2 degrees Celsius. One way of achieving emissions reductions is to adopt Market Based Instruments (MBIs) to incentivise the transition to a low carbon economy.

MBIs comprise one facet of climate finance, defined by the Seven Pillars Institute as ‘any financial service, instrument, vehicle or even regulation designed to mitigate, or adapt to, the effects of climate change’. Carbon pricing initiatives such as cap-and-trade schemes and carbon taxes fall under the domain of climate finance. The present review explores the ethical implications of carbon taxes specifically.

What is a Carbon Tax?

Households and businesses are currently charged inaccurately for fossil fuels and carbon-intensive goods because prices exclude the environmental and social cost of CO2 emissions. The US Federal Reserve Bank calls this a ‘fundamental market failure’ because, without proper price signalling, private agents will not be incentivised to reduce CO2 emissions. Consequently, unsustainable costs will be incurred to governments and other third parties.

Carbon taxes correct this failure by internalising the costs of carbon emissions into the price of fossil fuels and other products. A carbon tax is a Pigovian tax because it aims to return the external costs of burning carbon to the polluter. Consumers are then confronted with the ‘true’ costs of burning fossil fuels, which include both the private cost of extraction and processing and the external costs of environmental damage and social harms caused by elevated GHG emissions. Higher fuel prices will signal to businesses and households to switch to more cost-effective low-carbon products and invest in more energy-efficient technology and production. Carbon taxes can thus be used to ‘nudge’ CO2 emissions to a socially optimal level, where nudging refers to the process of using incentives to modify market behaviour.

Calculating a Carbon Tax

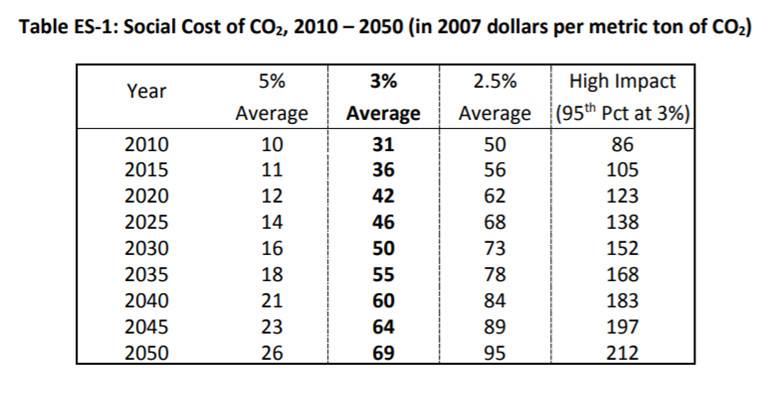

The most common metric for setting a carbon tax is the Social Cost of Carbon (SCC). The SCC is a per-tonne estimate of the long-term social costs caused by carbon emitted in a designated year over time. Costs include human health hazards, agricultural disruption, devaluation of investments and infrastructure damage, among other factors.

The SCC can also be used to calculate the benefits of emissions reduction efforts by estimating the economic damage prevented per each ton of carbon not emitted. In capturing the cost of externalities caused by carbon emission, the SCC essentially quantifies what it ought to cost today’s emitters to prevent future social and environmental harms. As GHG concentrations in the atmosphere continue to rise, the price of carbon is expected to increase to match the worsening projected damages.

Carbon prices are subject to substantial variance, ranging from less than US$1/tCO2 to US$139/tCO2, according to the 2018 World Bank Group’s report. One reason for this variance is different assumptions yield different estimations of the environmental damages caused by carbon emissions. For example, the discount rate and time span used greatly determine SCC estimates.

One commonly cited estimate was calculated by the Obama Administration’s interagency working group (IWG). The IWG’s (2016) estimate of SCC for 2020 is approximately $42 USD. The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development reported the average carbon price in 2018 across 42 countries was approximately $35 per ton. In contrast, the carbon tax recommended to prevent temperatures from rising more than 1.5 degrees Celsius by 2030 by the United Nations (2018) is $135- $5,500 per ton.

Figure 1. The IWG’s SCC estimates across three different discount rates from 2010-2050.

Use of Revenues Generated by Carbon Taxes

If a carbon tax is set sufficiently high as to alter fuel incentives and drive innovation and investment, it will generate significant revenue. For example, a tax of $49 per ton of carbon emissions (close to the IWG’s estimate of the SCC) in the U.S would generate approximately $2.2 trillion in net revenues over 10 years (Horowitz et al. 2017).

Carbon taxes can be revenue-neutral or revenue-positive. Most of the proceeds from revenue-neutral carbon taxes are redistributed amongst the population rather than retained by the government. The primary purpose of this redistribution is to mitigate the socially regressive effects of carbon taxes on lower-income households. The revenue can be returned through dividends, as in Canada’s carbon tax scheme which will return 90% of the revenue to its residents.

Alternatively, the revenue can be used to reduce existing distortionary taxes. For example, as carbon taxes increase over time, the money could be used to gradually phase out payroll taxes. Such ‘double-dividends’ may have economic benefits in addition to reducing emissions. Revenue-positive carbon taxes reinvest the proceeds in climate change mitigation projects.

Key Aspects of Implementing a Carbon Tax

Implementing an effective carbon tax requires consideration of a variety of factors. For example, carbon taxes vary by scope (substances targeted) and point of taxation. A fossil fuel tax could be levied upstream at the point of extraction and refinery, increasing prices downstream for households and businesses. They also vary by escalation rates, or the rate at which carbon taxes should increase over time to match increasing damage caused by climate change and incentivise emissions reductions. Policymakers also ought to consider the distributional impacts of carbon taxes, particularly on low-income households given the tax’s regressive nature.

Current National or Internal Carbon Tax Schemes

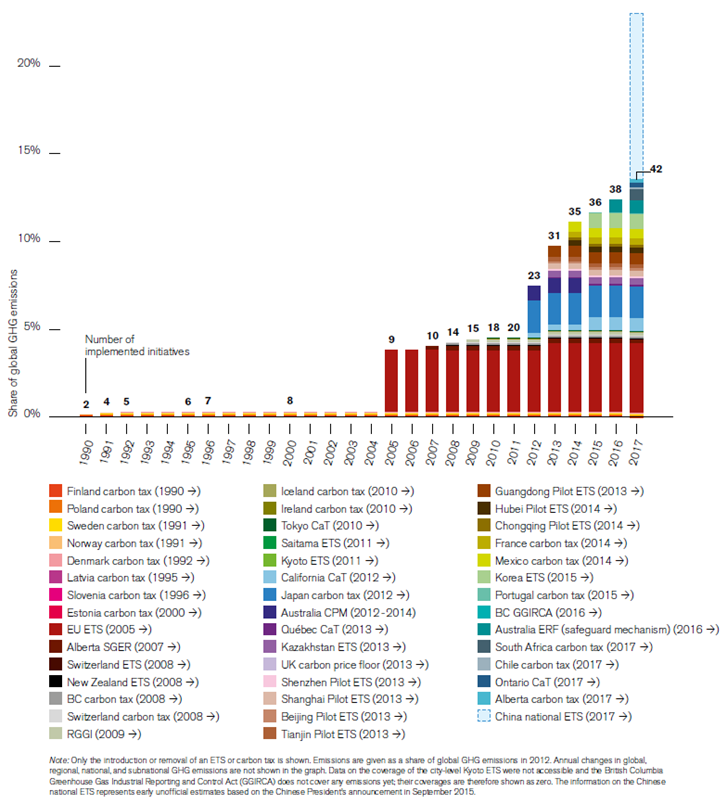

The first carbon taxes were implemented in the 1990s in Scandinavian countries such as Sweden Denmark, Finland and Norway. Carbon taxes were subsequently instituted in Switzerland, Iceland, Ireland, Japan, Mexico, Singapore and Portugal in the 2000s. Currently, there are also carbon taxes in British Columbia, Alberta, Latvia, Slovenia, Estonia, France, South Africa, the U.K, Argentina and Chile. The two largest emitters, China and the U.S, still lack a carbon tax.

Figure 2: proportion of global GHG emissions currently under a regional, national or subnational pricing scheme (World Bank 2016).

Evidence Carbon Taxes are Effective:

Countries that have instituted carbon taxes demonstrated substantial decreases in carbon emissions. For example, Sweden’s carbon tax was introduced in 1991 and reduced carbon emissions by 20% by 2018 (Jonsson et al. 2020) %. Coal consumption decreased significantly in the U.K after the introduction of a carbon tax in 2013 of $25 USD (Abrel et al.2019). Early evidence from carbon pricing schemes in British Columbia and wider Canada are promising. A comprehensive report analysing 16 of the world’s carbon tax initiatives concluded overall the available evidence indicates carbon taxes have contributed to reductions in energy use and carbon emissions’ (Nadel 2016).

Summary of the Pros and Cons of Carbon Taxes:

Pros of Carbon taxes:

- A carbon tax incentivises investment in low-carbon alternatives, such as renewable energy, which in turn may lead to technological innovation and the development of more efficient green energy.

- Raises revenue which may be used to fund climate mitigation and adaptation projects

- May have co-benefits for human health with reductions in water and air pollution from strip mines and increases in low-carbon transport options, such as walking and cycling.

- May have the potential to boost economic growth via the reduction of distortionary taxes

- Affords more market flexibility than government regulation because it is not technologically prescriptive and allows companies to formulate cost-effective ways of reducing CO2 emissions.

- Carbon taxes are administratively simple

Cons of Carbon taxes:

- There are difficulties with calculating the SCC and quantifying carbon emitted during production

- Companies may engage in tax evasion by moving production overseas to countries without a carbon tax, or ‘pollution havens’

- Introduces the possibility of free ridership, where all countries benefit from a reduction in GHG from a minority of countries with a carbon tax.

- A carbon tax may be expensive to administer

- There may be difficulties with political implementation due to public resistance to new taxes

- There may differences in the ability to pay between developing and developed nations

- A carbon tax is typically considered to be regressive without an effective revenue recycling scheme.

Ethics of Carbon taxes: The Polluter Pays Principle

At its core, a Pigovian tax is not merely an economic tool but also an instrument of distributive justice. By internalising the externalities of pollution into the price of carbon, emitters bear the burden of the harms for which they are responsible. The revenue raised from carbon taxes may be used to mitigate the effects of polluting activities, thus ensuring corrective justice. The latter depends on whether a revenue-neutral or revenue-positive tax is chosen.

Pigovian taxes rest upon the Polluter Pays Principle (PPP), which is both an economic and normative principle. The PPP is concerned with ensuring the social costs of pollution are borne by those responsible. As a normative doctrine, the PPP echoes Plato when he wrote: “If anyone intentionally spoils the water of another…let him not only pay for damages, but purify the stream or cistern which contains the water” (Khan 2015).

One of the issues with PPP is that it is difficult to apply in its absolute form. Carbon taxes are rarely true Pigovian taxes because it is difficult to calculate the true SCC. Further, it is politically challenging to implement a high carbon price which steadily increases to reflect increasing costs of climate change over time. Governments frequently set carbon taxes at a level sufficient to nudge the market toward reduced carbon emissions without generating enough revenue to offset the true social costs of pollution. The ethical obligation of emitters and their governments to compensate affected parties and mitigate climate change is seldom met. Nonetheless, the PPP can be applied to a range of ethical issues relating to carbon taxes and will feature in much of the following analysis.

Income Inequality

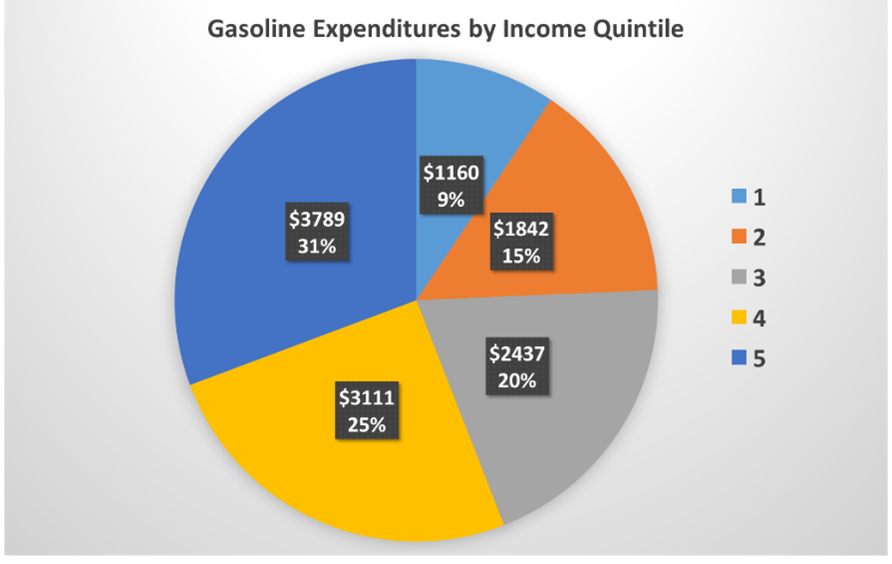

Domestic differences in income affect the way that a tax’s burdens are distributed. According to the PPP, polluters have a normative obligation to pay for the externalities of their actions. However, lower-income households will likely bear more of the burden of a carbon tax because they pay more per capita for energy. The concept of distributive justice employed in carbon taxes thus ought to apply to the consideration of how an increased carbon tax will affect low-income groups.

High-income groups spend substantially less per capita on basic needs such as domestic fuel than low-income households. According to a 2014 Bureau of Labour Statistics (BLS) U.S consumer expenditure survey, the wealthiest one-fifth of households only spent 2.7% of their income on petrol, while the lowest income households spent 10.8%. Further, high-income households tend to be carbon-intensive as they consume more luxury goods and services than low-income households. Per-capita emissions for the highest decile group in the U.K are 4.5 times greater for ‘private services and consumables’ than for the lowest income group (Gough et al. 2011).

Carbon emitted for luxury goods cannot be equated with carbon emitted for utilities such as transport, food, fuel and basic leisure. Since there is a limited amount of carbon that can be emitted to restrict increases in the global temperature to less than two degrees Celsius, higher decile households taking up more of this budget is unjust.

Figure 3. The proportion of gasoline expenditures by Income Quintile from the BLS Consumer Expenditure Survey, 2014.

Inequalities in carbon usage are compounded by the fact that high-income groups have a greater ability to adopt cost-cutting low carbon alternatives which reduce the impact of carbon taxes. For example, according to estimates by the Department of Energy and Climate Change (DECC) (2010), if carbon pricing were implemented, measures such as switching to renewable power sources and installing insulation could reduce utility bills by 25% in the U.S. Bills for those unable to afford these measures would increase by 2%.

A carbon tax will ensure those who are emitting more will pay more to offset the damages of their behaviour. For example, the BLS consumer expenditure survey 2014 found that households in the top income group spent 3.3 times as much on gasoline as the poorest 20%. High-income households will thus pay more carbon taxes than lower-income households overall.

However, since low-income households already pay more per capita for energy, imposing a carbon tax is likely to inflict a greater burden on these households. A study by Grainger and Kolstad in 2009 predicted the distributional impact of a $15 per ton of CO2 tax and found the burden for the bottom 20% of households on the income distribution would be between 1.4-4 times higher than for the highest-earning 20%. The way that the tax revenue is utilised will determine whether the tax’s net effect is regressive, proportional or progressive. For example, the Citizen’s Climate Lobby’s ‘fee and dividend’ proposal predicts that over half of U.S households would receive more through rebates than they would pay in taxes, rendering the policy progressive overall.

What to do with the Revenue

Carbon tax revenue use is a politically contentious issue. In the U.S. for example, surveys indicate conservatives and Republicans are more supportive of a carbon tax when revenues are used for deficit reduction or rebates (Nowlin, Gupta & Ripberger 2020). However, dividends may have a more socially progressive effect than deficit reduction. Evaluating these options in terms of their ethical significance involves analysing the trade-offs between fairness and economic efficiency.

A 2017 report from the Office of Tax Analysis (OTA) under the Obama Administration predicted that a refundable tax credit of $583 per person would benefit the lower 70% of households. Such a scheme would be socially progressive, ameliorating the burden of price increases for carbon-intensive goods on these households. From the perspective of climate justice, fee-and-dividend schemes serve the dual purpose of nudging the market toward low carbon alternatives while ensuring that those at the lower end of the income distribution are not unfairly burdened.

British Columbia’s carbon tax revenue system emulates a fee-and-dividend approach. Revenue is partially returned to the public in the form of a Climate Action Tax Credit of $174.50 per household to offset the burden of the carbon tax. Canada’s carbon tax rebates are predicted to financially benefit 80% of families. People tend to receive progressive revenue recycling options more favourably, possibly because they are perceived to be fairer than other options (Carattini, Carvalho & Fankhauser 2018).

Double-dividends reduce distortionary taxes which penalise desirable behaviours, such as income and labour taxes. They are purported to promote economic growth while simultaneously incentivizing emissions reductions, although empirical evidence for its effectiveness is lacking. Since double-dividends do not compensate lower-income households, the purchasing power of poorer households may not be protected. Further, double-dividends which reduce income taxes are predicted to benefit higher-income households more than lower-income households.

Further contention arises over whether carbon taxes should be revenue-neutral or revenue-positive. Some argue a revenue-positive carbon tax more fully meets the criterion for distributive and corrective justice. That is, as per the PPP, the polluter ought to pay to compensate for the damages incurred by their polluting actions. It thus makes ethical sense the revenue is reinvested in climate change mitigation and to compensate affected third parties. The Partnership for Market Readiness (PMR) estimates approximately 42% of global revenues from carbon pricing initiatives were reinvested in environmental projects in 2017/18. While a robust revenue-neutral carbon tax fulfils its function as an MBI to nudge the market toward investment in and transition to low-carbon alternatives, it does not deliver corrective justice.

Across these three revenue use options, competing conceptions of what is just, conflict. Fee-and-dividend initiatives are socially progressive, thus ensuring fairness while reducing emissions. Double-dividends are predicted to have economy-wide benefits, although they may not ensure that those at the lower end of the income distribution are protected from carbon price increases. Finally, reinvesting in climate change mitigation ensures that reparations are made for polluting behaviour. Since research indicates that attitudes toward carbon pricing schemes are sensitive to differences in revenue usage, policymakers ought to consider voter preferences when designing a carbon tax.

Distributive and Compensatory Justice: International Equity

Industrialised and developed nations are responsible for far more carbon emissions than poor and developing nations. According to Oxfam (2020), the world’s wealthiest 10% of people are responsible for more than 50% of carbon emissions between 1990 and 2015. While wealthier nations tend to be less vulnerable and more adaptable to the effects of climate change, poorer countries also tend to suffer more harms. In 2020, cyclones in India and Bangladesh caused $13 billion worth of infrastructure and crop damage, according to Indian officials. This ‘carbon inequality’ places normative obligations on developed countries to right the harms caused by their previous actions under the PPP.

Historical responsibility for carbon emissions is politically contentious. Some argue countries cannot be held responsible for carbon emitted prior to knowing the damages caused by their actions. Further, many of those emitting now are not necessarily those who were emitting previously. However, countries should make reparations for harms incurred after the consequences of emitting carbon were in evidence. The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) groups countries according to whether they are developed or developing. According to the argument that nations ought to pay from when the harm was known, Annex 1 countries (which comprise 38 developed states) ought to pay starting from the 1990s or 1980s. Given global carbon emissions increased by 60% from 1990 to 2015 (Oxfam 2020), this outcome holds developed nations accountable for a significant proportion of their emissions.

Environmental philosopher Alexandre Sayegh (2019) defines climate justice as ‘achieving the greatest possible emissions reductions while not preventing people from lifting themselves out of poverty’. The previous industrial activities of industrialised and developed nations now place constraints on the amount of carbon that can safely be emitted. While coal has the highest concentration of carbon, it is also one of the cheapest sources of energy and thus a viable option for developing nations pursuing economic growth.

It is unjust developing nations should be prevented from engaging in economic activities necessary to lift them out of poverty by the actions of developed nations, often while suffering greater harms because of climate change. The revenue raised through carbon taxes in developed countries has the potential to be used, in part, to make reparations, which would fulfil the obligation for corrective justice as per the PPP.

There are procedural issues with compensating developing nations. Many of the agents who would be paying tax for their current emissions are not the same agents who contributed to historical emissions. Sayegh (2019) suggests that the notion of restricted compensation be employed instead. According to this notion, the obligation to compensate for all historical harms is abandoned on the basis that this would be an enormously complex process and not all parties would be solvent. Instead, a portion of the revenues from carbon taxes would be redirected globally to ensure other nations’ right to energy was met.

Restricted compensation would be employed in tandem with other regulations and policies and offer only a partial solution to climate justice. Sayegh’s suggestion involves a trade-off between fairness and efficiency. It is more efficient to employ the notion of restricted compensation since it overcomes some of the pragmatic barriers to action, but it may mean forgoing some level of compensation due.

There are several ways restricted compensation may be achieved. Revenue could be donated to the Green Climate Fund, which funds developing countries to reduce emission via the development of clean energy and low-carbon alternatives in transport, agriculture and industry. This option simultaneously reduces emissions and compensates developing countries, thus strikes a balance between efficiency and fairness (Sayegh 2019). Revenue could also be invested in creating sustainable alternatives in developed countries, which could then be disseminated in developing countries. This revenue use would reduce the risk of harms resulting from climate change, including risks to human health, and provide employment via an emerging ‘green energy’ sector, thus providing co-benefits to developing and developed nations.

Carbon Leakage, Export Competitiveness, and International Equity

Imposing a carbon tax may increase the prices of carbon-intensive goods for export due to increases in energy costs. Countries without a carbon pricing policy in place may be able to produce equivalent goods at a lower cost and thus enjoy a competitive market advantage. Export losses in countries with carbon pricing initiatives to those without is called direct carbon leakage and can have negative economic outcomes. Indirect carbon leakage refers to domestic companies moving production offshore to nations without carbon pricing policies to reduce production costs.

The concern is countries without carbon taxes get to enjoy a competitive advantage while benefitting from a public good in the form of a reduction in emissions from countries with carbon pricing initiatives. Carbon leakage thus poses a free-rider problem resulting from a failure of international cooperation. Free ridership is fundamentally an issue of distributive justice, where the costs of maintaining a public good are incurred only to some while everyone benefits.

Although carbon leakage has been the subject of considerable political concern, the empirical evidence for the phenomenon is ambiguous. The majority of ex-post evidence is based on the EU ETS and carbon taxes. A report from the Carbon Market Watch Policy briefing (October 2015) concluded ‘to date, there has been no compelling evidence that EU’s climate policies are forcing companies to move abroad and recent academic studies indicate that this is unlikely to happen in the future even with a complete phase-out of free pollution permits’. One study from the London School of Economics concluded the risk of carbon leakage in the EU ETS in the future is so low, a ten-fold increase in the price of carbon would only result in a 0.5% fall in exports.

Partnership for Market Readiness (PMR) (2015) noted the dearth of evidence for carbon leakage does not mean it is not occurring. There may be alternative explanations for this effect; the short timescale in which carbon pricing schemes have been instituted may obscure patterns, the carbon price may be set too low, or carbon allowances to prevent carbon leakage may be sufficiently effective. Moreover, ex-ante modelling analyses ‘suggest a wide range of potential leakage rates indicating large uncertainty’ (PMR 2015). Political concern over carbon leakage thus draws more from the potential for carbon leakage than the evidence that actual leakage is occurring.

Public fear of the economic impacts of green policy may be manipulated by vested interests to undermine political support for such policies. Donald Trump (2017) mischaracterised the Paris Climate Accord when he told voters “China will be allowed to build hundreds of additional coal plants. So we can’t build the plants, but they can, according to this agreement. India will be allowed to double coal production by 2020 […] In short, the agreement doesn’t eliminate coal jobs, it just transfers those jobs out of America and the United States, and ships them to foreign countries.”

Trump is essentially arguing that committing to emissions reductions will enable free-ridership by other countries and promote economic development overseas at a cost to domestic industry and employment (Metcalf 2018). Such messaging may damage political support for carbon pricing schemes, allowing the U.S to eschew its ethical responsibility as per the PPP to pay for the externalities of its polluting industry. Regardless of the empirical evidence for or against carbon leakage, it has the potential to cause harm based solely on political fear of green policy.

This fear of carbon leakage may also manifest itself in policy accommodations for polluting industries to protect countries’ economic interests. For example, in the EU ETS, free allocations are given to sectors considered particularly at risk for carbon leakage. However, a policy brief by the Florence School of Regulation (2017) reported ‘an overly conservative criterion for identifying sectors at risk of carbon leakage meant that free allowances were given to installations which most likely were in fact not at risk’. Over subsidising polluters limits the environmental effectiveness of carbon pricing. Revisions have since been made to determine more efficient criteria for carbon leakage risk.

One solution for carbon leakage in carbon tax initiatives is to impose carbon border adjustments. Importing countries with carbon pricing policies would tax exporting countries at a rate determined by the amount of carbon emitted during production, while exports would be exempt. It is argued that the tax will incentivise exporting countries to leverage a carbon price to be exempt from carbon adjustment taxes.

One issue with carbon border adjustments is their feasibility under World Trade Organisation (WTO) rules. While WTO GATT Article II.2 (a) theoretically allows border tax adjustments, there are practical difficulties with implementing a carbon tax (Lee and Vaughan 2020). It is difficult to calculate and implement taxes for identical products produced using different levels of carbon. Failing to differentiate such products, however, threatens to undermine emissions reductions efforts by facilitating carbon leakage (Lee and Vaughan 2020).

The WTO principles of non-discrimination also come under siege where environmental and ethical considerations clash. WTO states ‘a country should not discriminate between its trading partners (giving them equally “most-favoured-nation” or MFN status); and it should not discriminate between its own and foreign products, services or nationals (giving them “national treatment”).’ Implementing carbon border adjustments threatens to discriminate against developing nations who rely on cheaper energy sources, such as coal. An MIT technology review notes that the model of economic growth adopted by many developing countries is a result of Western global dominance post-World War (Ravikumar 2020). Post-war international aid to promote economic growth in developing nations involved investments in fossil-fuel infrastructure (Ravikumar, 2020). Penalising such nations for relying on energy systems that the West promoted seems inherently unjust.

Distributive Justice: Intergenerational Equity

The current generation is uniquely situated to mitigate climate change. Where previous generations were unaware of the consequences of their actions and are unable to lessen or avoid the outcomes, future generations cannot be held responsible for the failure of their forbears to act and will have diminished resources to adapt to and mitigate climate change. Environmental philosopher Peter Singer (1972) argues we have an ethical obligation to reduce harm we can prevent without undue cost, even where we did not cause that harm. The present generation is thus burdened with a unique ethical responsibility.

This ethical imperative to act is compounded by the fact we only have a very limited time frame in which to change the trajectory of climate change. The Stern Review asserts ‘[t]he investments made in the next 10–20 years could lock in very high emissions for the next half-century, or present an opportunity to move the world onto a more sustainable path’ (Stern 2007, p. xxii). Future generations will face severe impediments to their ability to mitigate climate change, including diminished resources and difficulty coordinating political efforts in conditions of instability. Further, climate change is expected to become more determinate over time as global warming becomes a self-reinforcing process.

Harms to future generations must be factored into calculating the SCC. This is an enormously complex process which varies depending on assumptions such as timespan and discount rate. One component of calculating the SCC which reflects both normative and economic considerations is setting the social discount rate. The social discount rate is used to assign a value in the present to benefits or harms occurring in the future. According to the economic principle of a ‘pure time discount rate’, people tend to value the present over the future. A social discount rate of zero would place equivalent weight on the harms to future generations as on the costs borne by the present generations to prevent those harms.

Various ethical arguments have been employed as to why we ought or ought not to discount the SCC. Arguments from economic growth reason the SCC should be discounted because future generations will likely be wealthier than present generations. Arguments from moral equality argue that the time at which a person is born is a morally irrelevant trait, much like race or gender, thus the interests of future generations ought not to be discounted. Regardless of which ethical perspective is favoured, setting the discount rate too high will have adverse consequences for future generations, to whom we have an ethical obligation to prevent harm.

A further criticism relates to the fact that SCC is limited to a very narrow conception of intergenerational climate justice. It is primarily concerned with the PPP, which deals with the distribution of financial burdens. Ethicists have noted many of the underlying economic and normative principles of MBIs for climate change, such as the PPP and the ability to pay principle (APP) confine their considerations of intergenerational justice to burden-sharing.

Schuppert (2011) argues that a robust discussion of intergenerational justice ought to consider not only distributive justice but also future generations’ ability to fulfil their basic interests. Martha Nussbaum and Amartya Sen’s capabilities approach may embody such a conception of intergenerational justice. According to the capabilities approach, well-being consists in one’s capabilities to attain and embody certain qualities, such as to pursue higher education or to be physically fit. Moral weight is assigned to the freedom one has to develop one’s capabilities, which can be enabled or constrained by one’s environmental conditions, known as ‘conversion factors’. Runaway climate change is highly likely to present socio-political and environmental barriers to flourishing by constraining the capabilities of future generations. For example, the capability for physical health is likely to be impeded by pollution and water shortages.

Since the present generation has causal influence over the environmental conditions of future generations, we have a normative obligation not to constrict their capabilities in ways that prevent them from flourishing. Such a ‘thick’ conception of intergenerational justice cannot be captured by the PPP. Carbon taxes thus only deal with a thin conception of intergenerational justice and ought to be employed in conjunction with tools and normative frameworks which also consider the holistic well-being of future generations.

Politics

There are ethical issues with carbon taxes relating to politics. Political barriers to the implementation of carbon taxes delay action and have ethical implications regarding the failure to take responsibility for the harms of climate change. In many cases, self-interest and misinformation vie against ethical action. Carbon tax proposals have been repealed in Washington state (2016), Australia (2014), and Switzerland (2000 and 2015). To date, carbon taxes have only been implemented in democratic nation states.

One political difficulty with the implementation of carbon taxes is that public attitudes may be influenced by opposition from vested interests. For example, in Australia, public fears of the economic impact of the carbon tax were leveraged in media campaigns led by carbon-intensive companies (Carattini, Carvalho & Fankhauser 2018). Further, mistrust of the government may fracture support for a carbon tax. Australian Prime Minister Julia Gillard was perceived as having violated public trust when she instituted a carbon tax under pressure from the green party, having previously publicly declared that she would not. Voters often demonstrate a lack of trust in government to use carbon tax revenues fairly, which influences their attitudes toward carbon tax proposals (Carattini, Carvalho & Fankhauser 2018). Critical press coverage of Australia’s carbon tax likely compounded this mistrust, leading to the tax’s subsequent repeal in 2014.

A further political challenge is the sentiment of ‘no new taxes’ which has been present in the political sphere since George H. W. Bush promised it in 1988. Since the public tends to show a choice aversion to high taxes, governments are often reluctant to institute new taxes even when necessary for fear of losing public support. However, there is evidence to suggest that public resistance can be reduced by renaming carbon taxes ‘climate contributions’ (Carattini et al. 2017).

Although carbon taxes differ from, for example, income taxes in that they relate to an issue of considerable social significance, people still show concern about the personal financial costs the tax will impose (Brännlund and Persson, 2012). It is thus very difficult for policymakers to implement a carbon tax which is sufficiently high and rises over time to reduce emissions at the desired rate without facing considerable opposition. Setting the tax too high risks alienating voters, which is environmentally more detrimental than having a low carbon tax. However, there is evidence to indicate that public attitudes to carbon taxes may shift once the tax is implemented if the tax is initially set sufficiently low. Phasing in a carbon tax may therefore enhance the public acceptability of the tax (Carattini, Carvalho & Fankhauser 2018).

Distributive Justice: Transition Risk and Compensating Affected Parties

A further ethical issue with carbon taxes relates to transition risk. Where carbon taxes nudge businesses and households toward investing in low-carbon alternatives and switching to more energy-efficient options, they facilitate the transition to a low carbon economy. Intrinsically carbon-intensive sectors, such as coal, will likely suffer losses as a result. Workers in these sectors may be disproportionately burdened by carbon taxes, either through unemployment or wage cuts. Ensuring a just transition by providing support and compensation for these groups is imperative for climate justice. Failing to consider equity in the transition to new environmental policies can cause losses in social capital which have long-term consequences for climate change mitigation efforts.

Compensation and support may be offered in various ways. For example, in British Columbia, the CleanBC program reinvests carbon taxes paid by industry above $30 per ton of carbon in an incentives program for low-carbon alternatives for ‘regulated large industrial operations, such as pulp and paper mills, natural gas operations and refineries, and large mines’. The program is two-pronged, with revenue going toward both incentives and the CleanBC Industry Fund, which reinvests revenue into emissions reductions projects.

Given the coal sector in some Western countries such as Canada and the U.S has been shrinking with the rise of automation and natural gas, just transitions for the coal sector have already begun. The Canadian ‘Task Force: Just Transition for Canadian Coal Power Workers and Communities’ models a just transition. Measures were taken to protect workers, including income support, skills training and funding infrastructure for new industry in coal mining communities.

The Future of Carbon Taxes

The World Bank Report 2020 reports carbon pricing initiatives cover only 22% of global emissions, far less than the 15 gigatonne reduction required to meet the Paris Agreement goal of limiting increases in global temperature to less than two degrees (Vaughan 2019). As global temperatures rise, pressure to reduce emissions is projected to increase. Carbon tax ethics thus remain a contentious issue in public discourse, with The Toronto Sun reporting on in January 2021 that Canada’s carbon tax is allegedly having a regressive effect on Ontario residents; ‘According to independent, non-partisan Parliamentary Budget Officer Yves Giroux, 40% of Ontario households are already paying more in carbon taxes annually than they receive in rebates — double the national average — with costs escalating every year’. Policymakers ought to take into consideration the equity of carbon taxes both because they have an ethical duty to do so and because failing to do so could damage public support for much needed environmental policy.

Reference list:

Abrell, Jan, Mirjam Kosch, and Sebastian Rausch. “How Effective Was the UK Carbon Tax?-A Machine Learning Approach to Policy Evaluation.” A Machine Learning Approach to Policy Evaluation (April 15, 2019). CER-ETH–Center of Economic Research at ETH Zurich Working Paper 19 (2019): 317.

Auten, Gerald, and David Splinter. “Income inequality in the United States: Using tax data to measure long-term trends.” Washington, DC: Joint Committee on Taxation (2018).

Brannlund, Runar, and Lars Persson. “To tax, or not to tax: preferences for climate policy attributes.” Climate Policy 12.6 (2012): 704-721.

Carattini, Stefano, Baranzini, Andrea, Thalmann, Philippe, Varone, Frederic and Frank Vohringer . “Green taxes in a post-Paris world: are millions of nays inevitable?.” Environmental and Resource Economics 68.1 (2017): 97-128.

Carattini, Stefano, Maria Carvalho, and Sam Fankhauser. “Overcoming public resistance to carbon taxes.” Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change 9.5 (2018): e531.

Carbon Market Watch. “Carbon leakage myth buster.” Carbon Market Watch Policy Briefing (2015).

Council, Domestic Policy. “Technical Support Document:-Technical Update of the Social Cost of Carbon for Regulatory Impact Analysis-Under Executive Order 12866.” Environmental Protection Agency (2013).

Council, Domestic Policy. “Technical Support Document:-Technical Update of the Social Cost of Carbon for Regulatory Impact Analysis-Under Executive Order 12866.” Environmental Protection Agency (2013).

de Coninck, Heleen C. “IPCC SR15: Summary for Policymakers.” IPCC Special Report Global Warming of 1.5 ºC. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, 2018.

Economics, Vivid. “State and trends of carbon pricing 2016.” (2016).

Garden, Rose. “Statement by president trump on the Paris climate accord.” Energy Environ https://www. whitehouse. gov/briefings-statements/statement-president-trump-paris-climate-accord/(accessed September 25, 2019) (2017).

Goldstein, Laurie. “Trudeau’s carbon tax to hit Ontario families hardest”. Toronto Sun (January 2 2021)

Gore, Tim. “Confronting Carbon Inequality: Putting climate justice at the heart of the COVID-19 recovery.” (2020).

Gough, Ian, et al. “The distribution of total greenhouse gas emissions by households in the UK, and some implications for social policy.” LSE STICERD Research Paper No. CASE152 (2011).

Grainger, Corbett A., and Charles D. Kolstad. “Who pays a price on carbon?.” Environmental and Resource Economics 46.3 (2010): 359-376.

Horowitz, John, et al. “Methodology for analyzing a carbon tax.” US Department of the Treasury, Washington, DC (2017).

Jonsson, Samuels, Ydstedt, Anders, Elke Asen. ‘Looking Back on 30 Years Of Carbon Taxes in Sweden’. The Tax Foundation. (2020). URL: https://taxfoundation.org/sweden-carbon-tax-revenue-greenhouse-gas-emissions/. Accessed 3rd of January 2021.

Khan, Mizan R. “Polluter-Pays-principle: The cardinal instrument for addressing climate change.” Laws 4.3 (2015): 638-653.

Ki-moon, Ban. “Secretary-General’s Remarks at Workshop on the Moral Dimensions of Climate Change and Sustainable Development “Protect the Earth, Dignify Humanity”’. United Nations, 28 April 2015.”

Lee, Bernice and Scott Vaughan. ‘Is a Clash Coming When Trade and Climate Meet at The Border?’. SDG Knowledge Hub, 2020.

Lin, Boqiang, and Xuehui Li. “The effect of carbon tax on per capita CO2 emissions.” Energy policy 39.9 (2011): 5137-5146.

Lobby, Citizens Climate. “Carbon Fee and Dividend Policy.” (2018).

MacLeay, Iain. Digest of United Kingdom energy statistics 2010. The Stationery Office, 2010.

Marcantonini, Claudio,Teixido-Figueras, Jordi,Verde Stefano, Labandeira, Xavier. Free Allowance Allocation in The EU ETS. European University Institute (2017).

Metcalf, Gilbert E. ‘Paying for pollution: why a carbon tax is good for America’. Oxford University Press, 2018. Vaughan, Adam. ‘UN report reveals how hard it will be to meet climate change targets.’ New Scientist, 2019.

Nadel, Steven. “Learning from 19 Carbon Taxes: What Does the Evidence Show.” Proceedings of the 2016 ACEEE Summer Study on Energy Efficiency in Buildings, Pacific Grove, CA, USA (2016): 21-26.

Nowlin, Matthew C., Kuhika Gupta, and Joseph T. Ripberger. “Revenue use and public support for a carbon tax.” Environmental Research Letters 15.8 (2020): 084032.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Effective Carbon Rates 2018: Pricing Carbon Emissions Through Taxes and Emissions Trading. OECD Publishing, 2018.

Ravikumar, Arvind P. “Carbon Border Taxes Are Unjust”. MIT Technology Review (2020)

Sayegh, Alexandre Gajevic. “Pricing carbon for climate justice.” Ethics, Policy & Environment 22.2 (2019): 109-130.

Schuppert, Fabian. “Climate change mitigation and intergenerational justice.” Environmental Politics 20.3 (2011): 303-321.

Singer, Peter. “Famine, affluence, and morality.” Philosophy & public affairs (1972): 229-243.

Stern, Vivien, S. Peters, and V. Bakhshi. The stern review. Government Equalities Office, Home Office, 2010.

World Bank. 2018. The World Bank Annual Report 2018. Washington, DC: World Bank. © World Bank. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/30326 License: CC BY-NC-ND 3.0 IGO.”

Photo Courtesy of Winnipeg Free Press https://winnipegfreepress.com