Ethics Update on Cryptocurrencies

Beulah Samuel-Ogbu

This ethics update on cryptocurrencies is part of SPI’s continuing Bitcoin series.

Over 2000 cryptocurrencies have emerged in the last decade (Taskinsoy). Bitcoin being the most well-known. During the 2008 Global Financial Crisis, the (still) enigmatic Satoshi Nakamoto published a white paper entitled Bitcoin: A peer-to-peer Electronic Cash System. Several years since its inception, Bitcoin remains a nascent payment system. Traditional economists continue to find the concept difficult to grasp (Taskinsoy). Yet, cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin pose a challenge to the current economic order.

Some scholars see cryptocurrencies as a potential disruption to the established financial system. The other side of the debate deems this notion presumptuous. Cryptocurrencies are both highly volatile and far too unstable to be a dominant payment system. Therefore, cryptocurrencies remain largely an investment asset. Many are concerned about significant ethical issues as cryptocurrencies increase in prominence and popularity.

For instance, Elon Musk, Tesla’s founder, bought $1.5 billion worth of Bitcoin in February 2021. A few months later, one of the most prolific supporters of cryptocurrencies surprised investors when he tweeted that Tesla would suspend purchases of its vehicles through Bitcoin. The tweet caused the price of Bitcoin to tumble below $50,000 (Peterseil and Hajric). Musk cited environmental concerns as the reason behind his sudden decision. He stated Tesla’s concerns about the rapid increase of fossil fuel used for Bitcoin mining.

China accounts for more than 75% of all Bitcoin mining around the world (Hoskins).

Recently, the Chinese government summoned officials of major banks to reiterate a ban on cryptocurrency services. This sounded a death knell to Bitcoin’s surprising success in China. As a consequence, Bitcoin fell by 10%. Both China and Elon Musk have previously been significant supporters of cryptocurrencies. But their U-turns raises major ethical concerns about digital currency.

Cryptocurrencies Help the Global South

The lack of an institutionalised regulatory process cultivates an environment for illegal activity: 46% of Bitcoin transactions occur in the grey sector of society. Bitcoin is the preferred method of payment for criminal activity. Thus, are cryptocurrencies ethical? Answering this question is akin to examining whether a knife is an ethical utensil or not. The object or the digital currency in itself is not the problem. The ethics lies in but how it is used.

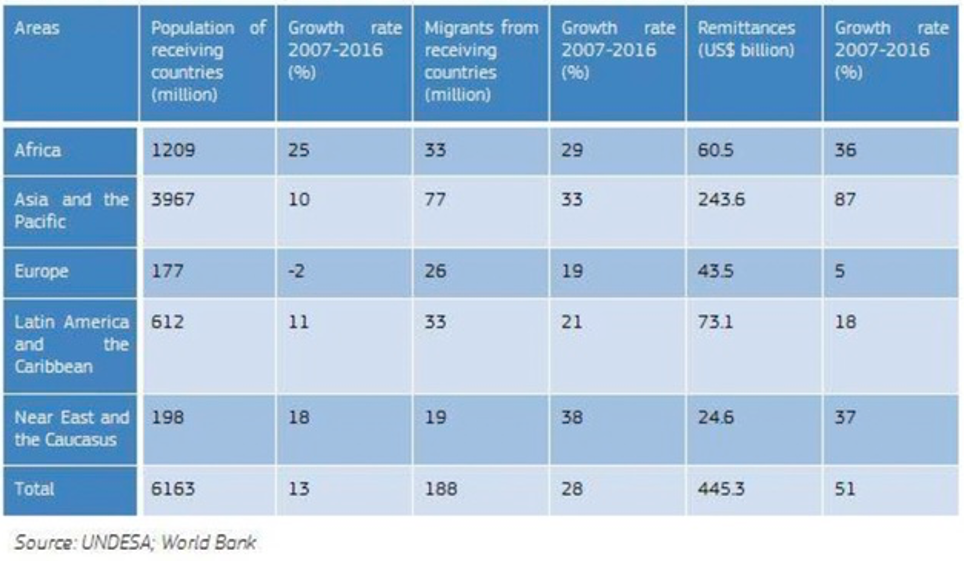

On the one hand, cryptocurrencies raise significant legal and environmental concerns. On the other, they provide tremendous benefits for the Global South. Bitcoin provides migrant workers from the developing world with an innovative medium of transferring remittances. Remittances are the funds migrant workers send to relatives in their home countries. According to the World Bank in the Remittance Market Outlook report, the costs of remittances are very high (Zulhuda and Sayuti).

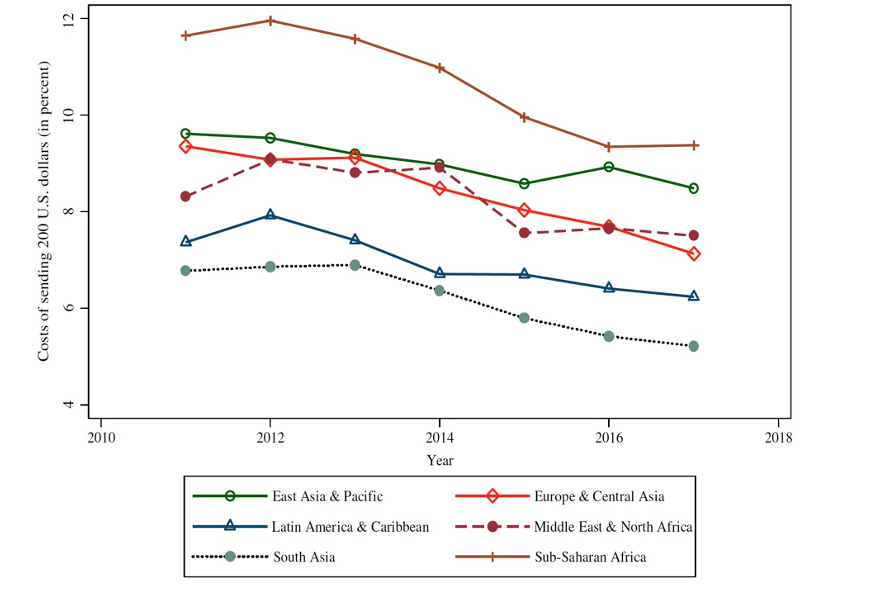

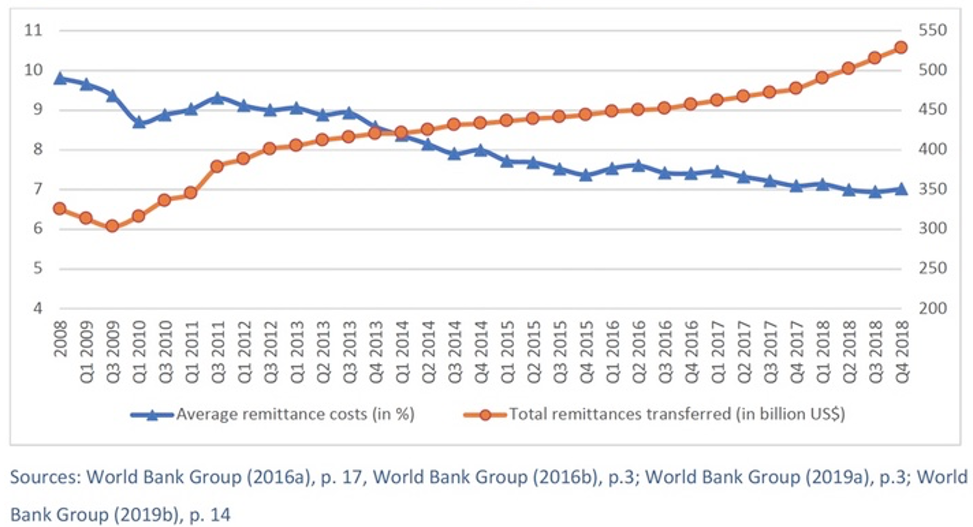

The estimated average price is 10 per cent of transactions (Beck and Peria). Remittances prices have a consequential effect on funds available for both migrants and their families. Transaction costs also have a subsequent impact on both the economic and social development of a migrant’s country of origin (Ahmed et al.). Cryptocurrencies such as Bitcoin are a novel solution to this problem. They offer low-income countries a method that potentially reduces the costs of cross-border payments (Rühmann et al.). Figure 2 shows from 2015 remittance costs have steadily decreased. This effect is due to the “entry of new players in the market, new technologies supporting digital payments and the progress made in improving financial inclusion” (Ahmed et al.).

However, the costs of remittances vary significantly depending on the region. For example, the cost had substantially decreased from 6.8% in 2011 to 5.2% in 2017. Sub-Saharan Africa remains the most expensive corridor for remittances. The average cost had fallen from 12% in 2011 to 9.4% in 2017. Despite the decline of prices, they continue to be above the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) targets of 3% (Ahmed et al.).

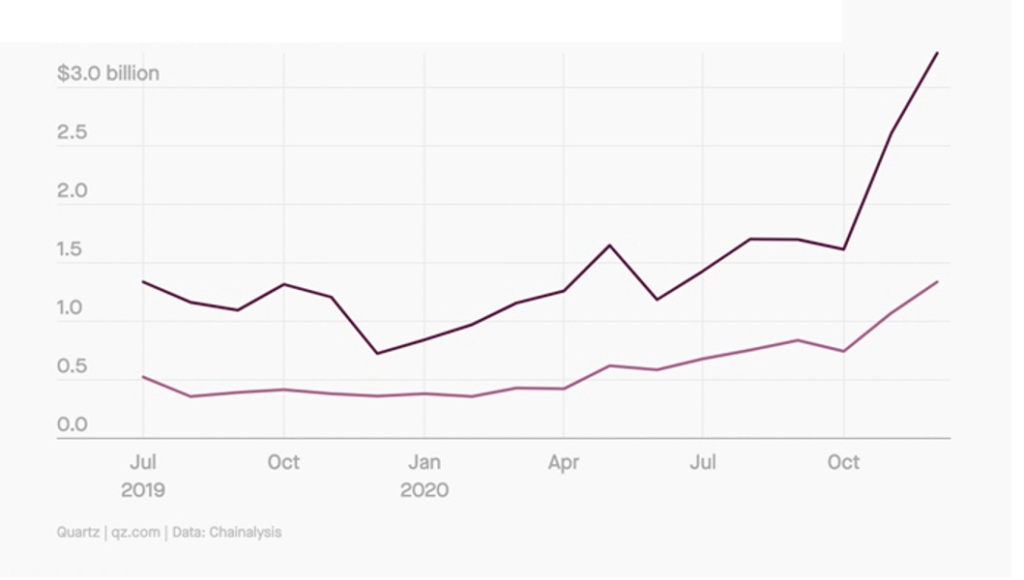

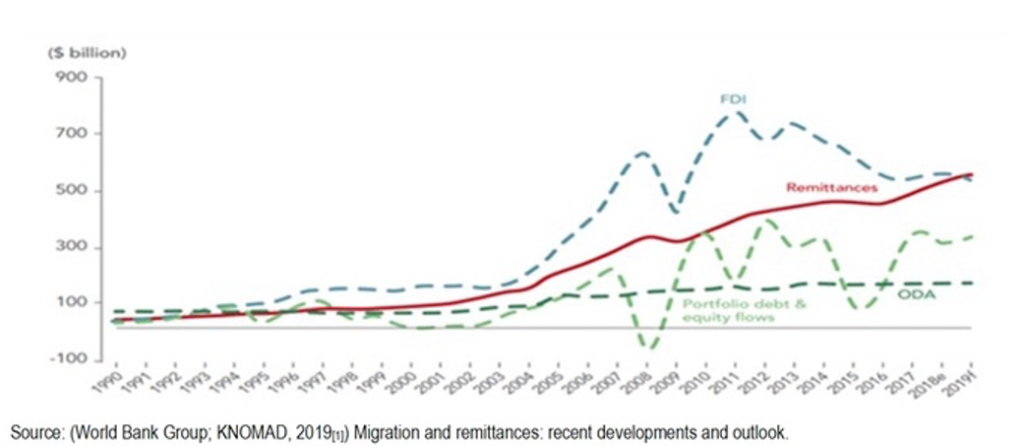

Figure 3 illustrates a surge in Bitcoin transfers to emerging markets (Wolverson). Bitcoin can help improve financial inclusion in low-income and middle-income countries. It provides an alternative for impoverished households with access to limited financial services. Despite these benefits, many issues obstruct cryptocurrencies from being the primary method of transferring funds across borders. Some developing countries lack the digital infrastructure to support cryptocurrency payments. Several countries do not accept Bitcoin. India encouraged its citizens not to use Bitcoin. The Bank of Thailand asked financial institutions not to engage in cryptocurrency transactions. Both Iran and Nepal officially banned cryptocurrencies. The lack of uniformity can negatively impact vulnerable people in the poorest regions of the world who rely on cryptocurrencies to send funds to their home countries.

The banning of Bitcoin is driven by ethical issues surrounding Bitcoin being the favoured payment method for criminals. Users have reported their Bitcoins stolen due to hacking. These issues potentially infringe consumer’s rights, including those from low-income countries. Cryptocurrencies pose significant ethical challenges in regards to their use in illicit activities. However, the ethics concerns arise from the lack of regulations, not from blockchain technology per se. Also, these challenges do not outweigh cryptocurrencies’ promises of significantly improving the quality of life for the world’s most destitute.

Remittances and Development

There are various definitions of remittances. The International Organisation for Migration sees remittances as a personal money transfer from migrant workers to their families in their home countries. The International Monetary Fund defines remittances as representing household income from a foreign country’s temporary or permanent movement (International Monetary Fund). The definition precludes any form of financial investment such as portfolio investment or real estate from a migrant worker’s country of origin managed by relatives (Rühmann et al.). For this paper, remittances are “a certain quantity of money sent regularly to families based in the home countries that are commonly used to improve elimination, access to health care, education, housing, raising entire communities over the poverty threshold” (Flore).

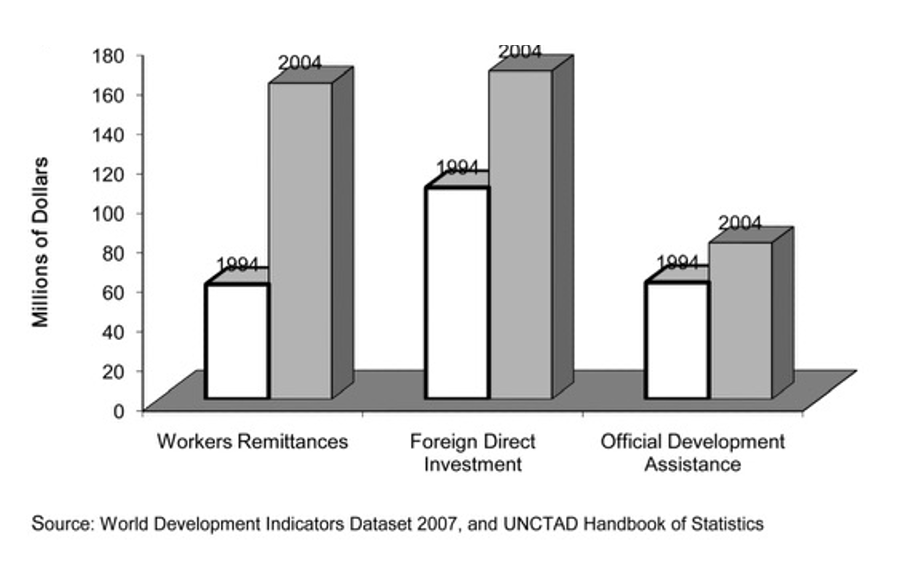

Remittances are a significant form of income for many low-income households in low and middle-income countries. For a number of developing countries, “remittances represent a major part of international capital flows, surpassing foreign direct investment (FDI), export revenues and foreign aid” (Fayissa and Nsiah).

A study conducted by the World Bank in 2006 found that recorded remittances grew significantly faster than FDI or development assistance. In 2018, remittance flows in low and middle-income countries increased by an estimated 8.5 per cent, reaching a record of $455 billion (World Bank Group). “Excluding China, remittance flows are also significantly larger than foreign direct investment (FDI) in LIMICs.” (World Bank Group).

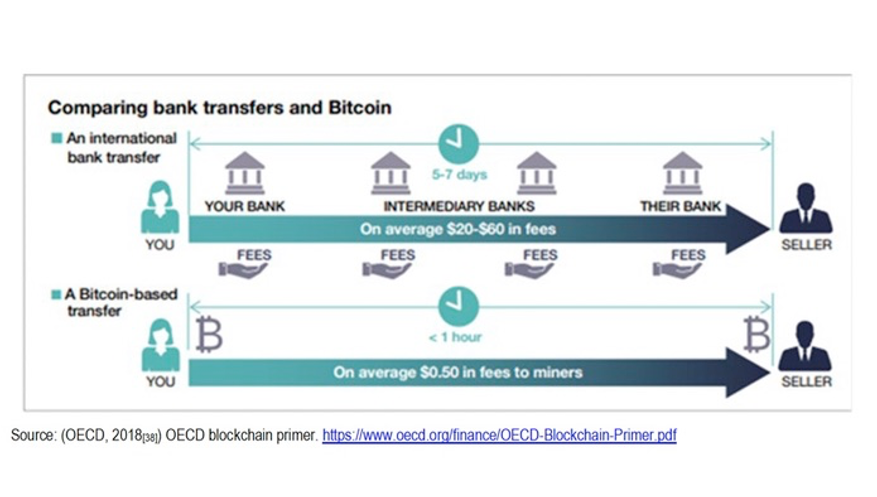

Remittances make a significant contribution to the GDP of developing countries. The funds drive economic growth and help finance investment in developing countries. They also raise household income and lead to higher levels of consumption. They have a multiplier effect on aggregate demand and output. Remittances are a preferable means of reducing poverty over development loans. Loans come with liability and obligations, while remittances do not (Pradhan et al.). For these reasons, multilateral institutions such as the World Bank, IMF, and the UN are eager to encourage remittances and reduce costs. Clearly, higher costs reduce the money that relatives of migrant workers can receive from transferred funds. In the first quarter of 2019, the average cost of transferring $200 to developing countries significantly decreased from 10% to 7%. However, this is still double the SDG targets of 3% by the year 2030. Banks are arguably the most secure form of transferring remittances. Banks can guarantee transfers will successfully cross-borders. Therefore transfer fails are extremely unlikely. However, in rare circumstances where the transfer does fail customers can be reimbursed (Metzger et al.). But banks are also the most expensive method for funds transfers. On average customers pay 10.9% per $200. Post offices are cheaper costing 7.6% (Ahmed et al.). Bitcoin is significantly cheaper at a rate of less than 0.0005 BTC (Bitcoin) transaction fee on the Bitcoin network. (Zulhuda and Sayuti). “Thus, a percentage point decline in remittance sending prices may result in up to $6 billion (USD) getting into the pockets of families and communities left behind and in need.” (Sirkeci and Přívara).

There are several reasons why banks and other non-digital currencies have substantially higher remittance costs. The lack of financial infrastructure is a contributing factor to high remittance costs. There are a “relatively high share of rural and remote areas which are not comprehensively covered by official remittances channels; outreaching remittances to clients in remote areas comes at some costs.” (Metzger et al.). Cash-based transactions demand at the first mile and the last mile of remittance delivery also plays a critical role in costs. A considerable amount of funds are used for consumption purposes rather than savings or investment. The lack of financial services drives the popularity of cash-to-cash practices over cash-to-account. A migrant worker hands the cash over to a money transfer operator. Her relatives receive the funds in cash as they do not possess a bank account. The customer pays for the cost of operating cash distributing points through commissions to local agents (Rühmann et al.).

Regulatory compliance is another contributing factor. “The regulatory and compliance procedures that include KYC requirements to curb money laundering and terror financing have raised the costs of operations for money laundering and terror financing.” (Rühmann et al.) However, this increase in compliance costs has increased the loss of money transfer operators. According to a study conducted by Thompson Reuters in 2016, $60 million was the average cost for finance firms meeting the Know Your Customer (KYC) obligations. Some firms spend up to $500 million on compliance with KYC. The increase in regulatory standards has led to many banks cutting ties with money transfer operators. This phenomenon is known as de-risking. Companies incur regulatory costs from registration requirements designed to deter fraudulent practices. The lack of uniformity regarding registration requirements among countries has led to cost increases. Additionally, smaller players are discouraged from entering the market thus distorting competition (Rühmann et al.).

Driven by technological innovations such as digital currencies entering the international money transfer markets, the cost of remittances has been decreasing. While the average MTO and bank remittance costs from 2014 to 2017 were static and Post Office costs increased, overall average costs decreased (World Bank Group 2019b) due to newcomers entering the market. The latter usually follow a strategy of low costs to enter the market and offer the customer an affordable alternative to bank channels. (Metzger et al.)

Cryptocurrencies as a Means of Transferring Remittances

For Venezuela, cryptocurrencies provide a better method of payment than the national currency. Poor financial institutions, hyperinflation, a weak economy and deteriorating payment systems attracted Venezuelans to Bitcoin. Bloomberg reported “the local market for Bitcoin broke a record in April 2018 reaching USD 1 million worth on one day alone.” (Rühmann et al.). Bitcoin has provided Venezuela with a faster and cheaper gateway for sending money home than traditional payment methods.

Nir Kshetri, in his paper, “Will Blockchain Emerge as a Tool to Break the Poverty Chain in the Global South?” argues there is evidence linking blockchain technology to Global South members overcoming economic, social and political challenges (Kshetri). For example, South African schools have used blockchain technology as a method of combating fraud and corruption. School donors can buy electricity using Bitcoin and the money is transferred to a blockchain-enabled smart meter without the need for an intermediary. In addition, donors keep track of how much electricity is being consumed and calculate the amount of power their donations buy (Kshetri).

Digital technologies play a vital role in developing countries. Even when poor households in developing countries lack electricity and drinking water, they still have access to mobile phones (Pilkington and Crudu). Supported by existing digital technology, cryptocurrencies seem to be a credible solution in financially including the unbanked. But cryptocurrencies in developing countries face significant challenges. The last-mile delivery problem plays a critical role in the rising remittance costs. It also creates an issue in transferring funds through digital currencies. Cash remains the most widely used payment instrument in many developing regions of the world, such as Sub-Saharan African Countries. According to the World Cash Report 2018, ATM withdrawals has experienced increasing growth. This indicates a growing need for cash in day-to-day transactions. A small number of countries have been able to reduce the prevalence of cash; most of those countries are in Europe and the Oceania region. Thus, even though Bitcoin is an efficient means of transferring funds between mobile devices, the demand for cash withdrawals would require cash-out locations or local exchanges. The last miler would need to possess the necessary liquidity to convert cryptocurrencies to cash. Not all countries have the liquidity to meet local demand or the trust to absorb Bitcoin. There is also a countdown involved in the conversion of cryptocurrencies to cash (Rühmann et al.).

The digital divide has a considerable effect on the use of Bitcoin to transfer remittances. Although mobile technology is prevalent in developing countries, there is a lack of internet access. According to the GSMA State of Mobile Internet Connectivity report 2019, just over 40% of the population of low and middle-income countries are connected to the internet, compared to almost 75% of the population in high-income countries. The mobile industry connects over 3.5 billion people to the internet (47% of the world population). Therefore, more than half the world’s population are still unable to realize the social and economic benefits that mobile internet can enable. If current trends continue, more than 40% of the population in low and middle-income countries will still be offline in 2025. (Rühmann et al.) As cryptocurrencies are heavily reliant on accessible digital infrastructure, relatives of migrant workers may find difficulty in accessing Bitcoin from a lack of internet connectivity.

In addition, “Using Bitcoin as a unit of account is very difficult due to its 8 decimal places and odd pricing numbers. Further, a currency should function as a medium of exchange and should thus be a commonly accepted means and payment method for current transactions. While the number of merchants accepting Bitcoin is increasing, it’s still far from crossing a minimum threshold to be of relevance. Lastly, the price volatility and the insecurity about future performance rules out Bitcoin taking over the function of the store of value and the medium of deferred payments which both require (expected) long term stability. The volatility and instability of Bitcoin discourage creditors from accepting Bitcoins as a medium to fulfil medium- and long-term contracts, e.g. debt contracts (Metzger et al.). As a nascent form of currency, Bitcoin’s market share of remittance transfers is growing but still very limited. The advantage of a Bitcoin transaction being complete in about ten minutes and the very small transfer fee qualify Bitcoin as an intermediary between fiat currencies. According to Metzger et al, Bitcoin can serve as the settlement currency because even if the settlement sum is high, there is no effect on the cost since the transfer fees are calculated by file size and not by the value transferred (Metzger et al.).

Bitpesa is an African remittance start-up that may serve as a model for cryptocurrency money transfers. The company uses Bitcoin for international money transfers and connects to a widely accepted payment system M-Pesa in the transaction process. Through their Bitcoin platform, Bitcoins can be sent from over 85 countries to Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda and Nigeria. After receiving Bitcoins from customers, the company then converts them into the local currency. The receiver decides whether the Bitcoin should be paid out in cash or sent to a mobile M-Pesa wallet. The transaction fee for the conversion is 3% per transfer. Cryptocurrencies, if utilized properly, can be a considerable benefit for low-income households in developing countries. However, successful application depends on accessible digital infrastructure and considerable infrastructure changes need to be made to facilitate cryptocurrencies.

Illicit Activities and Consumer Rights

Cryptocurrencies are not accountable to a central authority. The lack of regulation and an accountable central authority is arguably one of the most significant ethical concerns for governments and scholars on cryptocurrencies. It’s a critical reason why several countries have banned Bitcoin. Bitcoin provides customers with a payment system that can circumvent institutionalised regulatory processes. Consequently, the payment system has cultivated an optimal environment for illegal activity. Bitcoin appears to be the preferred method of payment for criminal activity. The security of anonymity and the lack of central authority make Bitcoin an ideal instrument for conducting illicit transactions. For example, an underground black-market website known as Silk Road emerged as the most sophisticated and extensive criminal marketplace on the Internet. In October 2013, The Guardian reported that US authorities immediately shut down Silk Road’s operation and confiscated all Bitcoins in a seizure totaling 26,000 BTC, worth $3.6 million at the time of the transfer (Zulhuda and Sayuti).

Individuals who value their privacy and want to cloak transactions in obscurity have taken particular interest in cryptocurrencies. They have become a means of evading and hiding other nefarious activities such as terrorism, money laundering, child pornography and human trafficking (Middlebrook and Hughes).

The lack of supervision places consumers at risk. Scholars and policymakers question whether cryptocurrencies adequately protect consumers rights. The safety issues lie in the fact that blockchain technologies are relatively new, with cryptocurrencies still at the infant stage. As such, the payment system fosters significant security issues. If a transaction is made through Bitcoin, it is irreversible. Users’ Bitcoins can be lost or stolen. For example, Stefan Thomas, a Bitcoin user, accidentally forgot his account password and erased two copies of his e-wallet. He lost 7,000 Bitcoin worth $140,000 in 2011 (Zulhuda and Sayuti). Bitcoin theft has significantly increased through hacking and malware. The Bitcoin Foundation has warned users about the loss of Bitcoin money by hacking Android wallet applications (Zulhuda and Sayuti).

There is a lack of consensus on how to regulate cryptocurrencies. Some countries, such as Nepal and Pakistan, have called for a complete ban. Venezuela avidly supports Bitcoin. While for other countries such as Denmark the place of cryptocurrencies remains ambiguous. Some scholars, who support the concept of cryptocurrencies, call for a more structural regulatory framework. Not regulating poses a challenge to developing countries as households’ funds may not be adequately protected. The threat of funds being lost by malware or hacking can place individuals with limited resources in precarious positions. Inadequate consumer protection may cause households to lose faith in the platform as a viable payment option. However, the lack of uniformity in how cryptocurrencies are regulated infringes on their ability to transfer remittance . The different rules for its uses would make it difficult for migrant workers to use the currency to transfer funds across borders. If cryptocurrencies are to be regulated there needs to be a universal response. The question of whether to regulate Bitcoin has been examined in Georgette Fernandez Laris’s paper Bitcoin: To Regulate or not to Regulate?

While the criminal activity surrounding cryptocurrencies is a reason for ethical concern, for developing countries, digital currencies provide a critical method for promoting development. Like knives, cryptocurrencies are neither good nor bad, but if appropriately utilised, cryptocurrencies may drastically improve the lives of the world’s most vulnerable individuals.

Bibliography

Ahmed, Junaid, et al. “Sending Money Home: Transaction Cost and Remittances to Developing Countries.” The World Economy, Mar. 2021, p. twec.13110. DOI.org (Crossref), doi:10.1111/twec.13110.

Beck, Thorsten, and Maria Soledad Martinez Peria. What Explains The Cost Of Remittances ? An Examination Across 119 Country Corridors. The World Bank, 2009. DOI.org (Crossref), doi:10.1596/1813-9450-5072.

Fayissa, Bichaka, and Christian Nsiah. “The Impact of Remittances on Economic Growth and Development in Africa.” The American Economist, vol. 55, no. 2, Nov. 2010, pp. 92–103. DOI.org (Crossref), doi:10.1177/056943451005500210.

Flore, Massimo. “How Blockchain-Based Technology Is Disrupting Migrants’ Remittances: A Preliminary Assessment.” Joint Research Centre (JRC), the European Commission’s Science and Knowledge Service, p. 46.

Hoskins, Peter. “Tesla Will No Longer Accept Bitcoin over Climate Concerns, Says Musk.” BBC News, 13 May 2021. www.bbc.co.uk, Hoskins, Peter. “Tesla Will No Longer Accept Bitcoin over Climate Concerns, Says Musk.” BBC News, 13 May 2021. www.bbc.co.uk, https://www.bbc.com/news/business-57096305..

International Monetary Fund, editor. Balance of Payments and International Investment Position Manual. 6th ed, International Monetary Fund, 2009.

Kshetri, Nir. “Will Blockchain Emerge as a Tool to Break the Poverty Chain in the Global South?” Third World Quarterly, vol. 38, no. 8, Aug. 2017, pp. 1710–32. DOI.org (Crossref), doi:10.1080/01436597.2017.1298438.

Metzger, Martina, et al. Migrant Remittances: Alternative Money Transfer Channels. p. 38.

Middlebrook, Stephen T., and Sarah Jane Hughes. “Regulating Cryptocurrencies in the United States: Current Issues and Future Directions.” William Mitchell Law Review, vol. 40, 2014, p. 37.

Peterseil, Yakob, and Vildana Hajric. “Bitcoin Dips below $50,000 as Musk Calls Energy Usage ‘Insane.’” Aljazeera, 13 May 2021, https://www.aljazeera.com/economy/2021/5/13/bitcoin-dips-below-50000-as-musk-calls-energy-usage-insane.

Pilkington, Marc, and Rodica Crudu. “Blockchain and Bitcoin as a Way to Lift a Country out of Poverty – Tourism 2.0 and e-Governance in the Republic of Moldova.” SSRN Electronic Journal, 2016. DOI.org (Crossref), doi:10.2139/ssrn.2732350.

Pradhan, Gyan, et al. “Remittances and Economic Growth in Developing Countries.” The European Journal of Development Research, vol. 20, no. 3, Sept. 2008, pp. 497–506. DOI.org (Crossref), doi:10.1080/09578810802246285.

Rühmann, Friederike, et al. “Can Blockchain Technology Reduce the Cost of Remittances?” OECD, 2020, p. 36.

Sirkeci, Ibrahim, and Andrej Přívara. Remittances Review. 2017, p. 10.

Taskinsoy, John. “This Time Is Different: Facebook’s Libra Can Improve Both Financial Inclusion and Global Financial Stability As a Viable Alternative Currency to the U.S. Dollar.” SSRN Electronic Journal, 2019. DOI.org (Crossref), doi:10.2139/ssrn.3434493.

Wolverson, Roya. “Bitcoin Draws Millions of Workers Sending Their Money Abroad.” Quartz, 2021, https://qz.com/africa/1983610/bitcoin-draws-millions-of-workers-sending-their-money-abroad/.

World Bank Group. Migration and Remittances: Recent Developments and Outlook. World Bank, Washington, DC, 2017. DOI.org (Crossref), doi:10.1596/28444.

Zulhuda, Sonny, and Afifah binti Sayuti. “Whither Policing Cryptocurrency in Malaysia?” IIUM Law Journal, vol. 25, no. 2, Dec. 2017, pp. 179–96. DOI.org (Crossref), doi:10.31436/iiumlj.v25i2.342.